The projected merger between the Resistance Movement (Resist) and the Socialist Labour Party (SLP) is an intriguing but possibly fruitful endeavour. Resist was founded in 2020 in the aftermath of the defeat of the Corbyn movement and the rise to the Labour leadership of Keir Starmer. Its most prominent founder is Chris Williamson, the former Labour MP for Derby North, and for a while Shadow Minister for Local Government under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. Chris W was the most outspoken and principled left-wing former MP by far to emerge from the Labour Party in the Corbyn period, the only one to sharply criticise the conciliation toward the Blairite right wing that doomed Corbyn to defeat by his extremely ruthless and utterly unscrupulous Blairite and Zionist opponents.

His refusal to bow the knee to the witchhunt led to his being suspended three times on trumped-up and mendacious charges in 2019 by the Labour Party. When he defeated the second of these suspensions, in the High Court where it was declared unlawful, he was then suspended for a third time in a blatant manoeuvre to evade the court judgement. He was blocked from standing for the Labour Party in the December 2019 General Election and stood as an independent, losing his seat (which of course was the whole purpose of the corrupt suspensions in the first place).

The charges involved innuendos of ‘anti-Semitism’ by the Labour Party’s powerful Zionist wing, who defend the mass ethnic cleaning of the Palestinians from their homeland in 1948, and the Israeli state ever since, against the supposed ‘terrorism’ of its victims, and systematically smear anyone who stands up for Palestinians as in some way motivated by hatred of Jewish people. These lies do not stand up to a moment’s scrutiny by any objective person, but objectivity in the Labour Party is in very short supply.

The Tory/Blairite-infested Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), the quango which in 2021 produced a fraudulent report on ‘anti-Semitism’ aiming to smear the Corbynite left, originally also aimed to smear Chris Williamson by denouncing him as some kind of perpetrator in their report. But unlike others in Labour, who were sluggish to react to this in fear of the malign influence of Starmer and the Zionists, Chris made it very clear to the EHRC that any such smears would result in an all-out political and legal war with himself. The witchhunting quango, which has itself been credibly accused of gaslighting and playing down institutional racism on behalf of Boris Johnson’s government, backed off and removed their draft nonsense about Chris from their report before it was published.

There is a long tradition of pro-imperialist and racist politics in Labour, including support for Zionism and various other forms of colonialism, originally rooted in the pro-imperialist labour bureaucracy, and even more among the overtly bourgeois, neo-liberal and corporate-funded elite layer of political mercenaries that were assembled and empowered by Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair. The later layer came to dominate Labour in the period between the defeat of the 1984-5 miners’ strike and the leftist, working class political revolt against austerity that put Jeremy Corbyn into the Labour leadership in 2015. This revolt was at bottom a ferocious clash between a regenerating mass base for this bourgeois workers party, and the reinforced neoliberal political bureaucracy of the Blairites, a clash that was always likely to be bloody. As it proved, and Corbyn proved utterly inadequate to fight back against the neoliberal counterattack.

Chris Williamson is virtually the only Labour parliamentarian who has come out of the Corbyn period with his integrity as a socialist intact. In fact, he has been obviously radicalised by the experience and has even taking to explaining why the Labour Party is not a vehicle for socialism by citing the famous remark of Lenin that the Labour Party, “though composed of workers”, is a “thoroughly bourgeois party” led by “reactionaries, and the worst kind of reactionaries at that”. This should not be taken to imply that Chris has embraced revolutionary Marxism tout court, but certainly indicates a strong trajectory away from Labourism in a more left-wing direction that is likely to become expressed in mass politics in the next period. As expressed in his condemnation of Zionism, which is getting stronger and clearer as time goes on, and his principled and courageous speaking out in defence of the population of the Donbass, under attack from Ukrainian Nazis since 2014, and defence of the Russian Special Military Operation in Ukraine to stop the genocidal NATO-inspired and -funded Maidan genocidal ethnic war against the Russian-speaking Donbass people.

Can Resist revive the SLP?

What is clear from Chris’s recent autobiographical work, Ten Years Hard Labour, is that he is one of the most principled and radical figures that have ever broken to the left from Labour and is determined to play a unifying role in trying to put together a new working-class party initiative. Which brings us onto the proposed unification of the Resistance Movement with the Socialist Labour Party, which was founded on the initiative of Arthur Scargill, then the President of the National Union of Mineworkers, on May Day 1996.

The SLP was founded as a belated response to the takeover of the Labour Party by the supporters of Neil Kinnock and then his protégé and continuator, Tony Blair. Kinnock was the traitorous neoliberal ex-‘left’ MP and loudmouth from the 1970s, who when elevated to leader in the mid-1980s, spent an enormous amount of effort stabbing the NUM in the back in their great 1984-5 strike, which was against Thatcher’s massive pit closure programme which destroyed the British coal mining industry, the employer of around 190,000 miners, who were a key strategic backbone of the labour movement in Britain. The SLP showed much promise in the immediate aftermath of its formation, attracting many serious left-wing and class struggle inclined militants, with a variety of leftist political views. Unfortunately, it rapidly became clear that Arthur Scargill and the layer around them did not have the political capacity to lead the membership they had attracted. For all their history of exemplary trade union militancy, and their socialist aspirations, their education in the left wing of the bureaucracy and their background in official communism led them to see many of those who joined the SLP as simply a threat.

So right from the beginning, the SLP was saddled with a bureaucratic constitutional clause that banned any kind of dual affiliation by members with any other trend on the very fragmented left, or even implicitly any kind of factional alignment within the SLP. The latter was very selectively enforced: those in clearly factional groupings close to the leadership got away with blatant breaches of the same principles. The outcome was a series of tragi-comic purges of much of the membership, which gutted the SLP of much of its potential to offer an alternative to the Blairised Labour Party, and meant that as the 2000’s wore on, the SLP’s challenge to Blairism was overshadowed by those of other forces, such as the Socialist Alliance and RESPECT, which actually inflicted some defeats on the Blairities.

The big problem of those other forces was that those large sects on the ‘far left’ who played a major role in building them saw then as temporary coalitions and arenas to build their own projects, not the progenitors of a new working-class party. So, they managed to mislead and disappoint a generation of left militants whom the SLP was simply unable to reach because of its bureaucratic sterility. George Galloway personified the ‘what might have been’ of the SLP in the 2000s, when he led a section of the Labour Party’s mass base among the oppressed Muslim immigrant population into confrontation with Blair over Iraq, and won some victories and near victories, it was the SWP who were able to benefit from it and ultimately mislead and shipwreck it, while the SLP were nowhere near being able to address this layer. The SLP thus remained marginal all through not only the resistance to Blair, but also the Corbyn period, which also might have been expressed differently if the SLP had done what it originally aspired to do.

The attempt to revive the SLP for a new generation as a unifying force for the ex-Corbynite layers who are looking for a focus of resistance to build a new party around is a positive and worthwhile endeavour, which we hope is able to succeed. The ethos that Chris Williamson has been fighting for since he left the Labour Party has been an attempt to play a unifying role among the existing fragments of the working class left outside the Labour Party. He has worked alongside TUSC, and with the Workers Party of George Galloway and Joti Brar, in election campaigns that have attempted to confront the Starmerites, trying to overcome the obvious flaws of those initiatives and play a unifying role. The attempt to unify with the SLP and revive this flawed but originally excellently driven initiative is in the same mould and has a good chance of success. Though Chris’s thrust in seeking wider democracy and inclusiveness of the left and the working-class grassroots (his Democracy Roadshow in Labour; his activity since) appears at odds with the practice of the SLP, his project really is in tune with what the SLP should have and could have been, and obviously such a figure from today’s Labour left seeking to join and revive it is something that the SLP leadership ought to regard as a big compliment.

The Miners’ Unions and Class Struggle in Britain

The Mineworkers Union, from which the SLP emerged, had been the strongest union in Britain through most of British capitalism’s history, in various stages of their evolution, and reactionary bourgeois governments throughout British history have sought to defeat the working class by defeating the miners. This happened in 1926, when a General Strike to defend the miners against savage pay cuts was betrayed by the leaders of the TUC after 10 days, just as it was becoming insurrectionary.

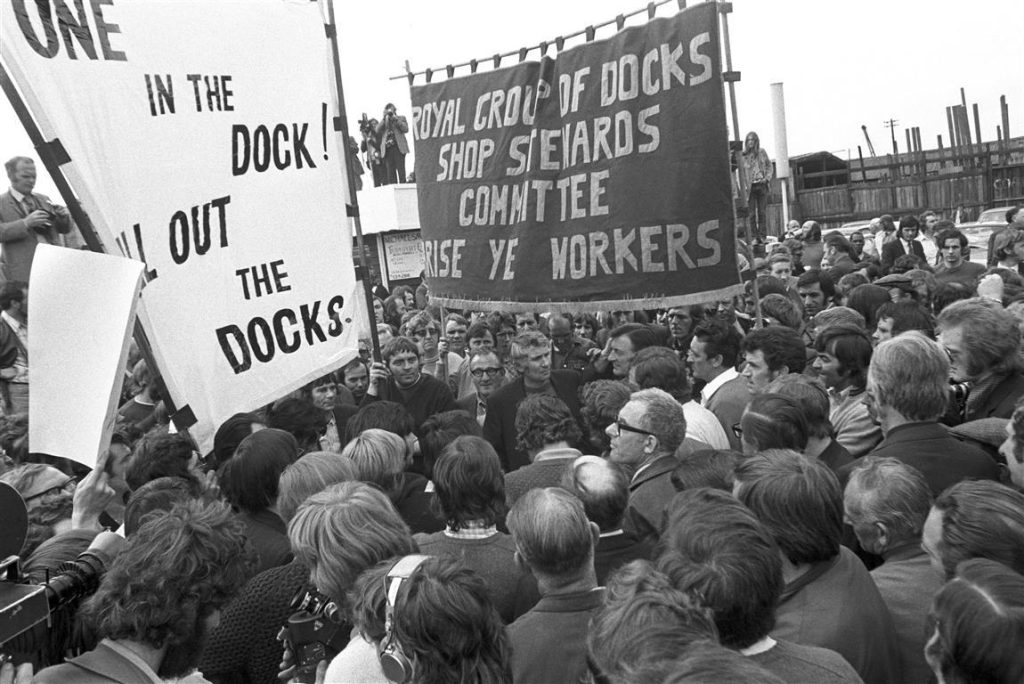

In the early 1970s, as the post- WWII economic boom came to an end and the era of neoliberal attacks on the working class was just beginning, the response of the British working class was to fight back through its then-very strong trade union movement. The miners’ union played a central role in this fightback, as symbolised by the victory of a determined mass picket of a huge coke depot in Saltley, Birmingham, where the then Yorkshire NUM President, Arthur Scargill, led his men in facing down the cops and closing the gates of the depot, when they were joined by enormous numbers of workers particularly from motor and engineering factories in Birmingham (most of which were also later destroyed by Thatcher). Saltley Gates became a symbol of working-class courage, militancy and solidarity. Thanks to such militant methods, the 1972 strike against inflation and erosion of miners pay ended in substantial victory.

This whole affair was part of a huge, wider wave of working-class militancy that at its peak led to the TUC being forced to call a general strike to free five dock workers who the Tory government and Judges tried to jail for defying them. The government belatedly discovered an obscure official, the ‘Official Solicitor’ who had the power to release them. And he did!

Another miners strike, in early 1974, against the erosion of miners (and railworkers) pay forced the anti-union Heath Tory government out of office. Two general elections took place in 1974, resulting in first a minority Labour government in February, and then one with a small parliamentary majority in October 1974. This unprecedented period of working class victory was followed by the interregnum of the Wilson-Callaghan Labour governments of 1974-79, where the working class upsurge was first headed off with a series of reforms, including the repeal of Heath’s Industrial Relations Act, and then regimented into the straightjacket of the ‘social contract’ – wages held down by ‘agreement’ with the trade union bureaucracy while another bout of inflation, triggered off by the Vietnam and Middle East wars – coursed through the system. Neoliberalism made its first tentative beginning in this period with chancellor Denis Healey’s wave of cuts to public services to procure a loan from the IMF. These attacks gradually built up an enormous sense of rage in the working class, as well as leading to the growth of the far-right racist National Front party. Finally, this exploded in a leaderless strike wave, the Winter of Discontent, in 1978-9, which sank the weak Callaghan Labour government and laid the basis for the election of an even more vicious Tory government under Margaret Thatcher, who really did impose neoliberalism in Britain.

The Tories prepared their revenge for 1974 very carefully: they picked off less powerful sections of the working class in piecemeal fashion throughout Thatcher’s first term, and only after she was re-elected in a wave of imperial chauvinism over the 1982 Malvinas war, did they dare take on the miners. With a massive pit closures programme, imposed at the end of winter in early March after they had stockpiled huge amounts of often imported coal. A militarised police force was used for strikebreaking on a massive scale. And Kinnock, the new leader of Labour after the 1983 election defeat, fought long and hard to isolate the miners and ensure that resistance to Thatcher would not become generalised. When other sections of workers, such as dockers in two strikes in the Summer of 1984, came out effectively in support of the miners, Kinnock worked overtime to ensure they were sent back to work, and to thwart the possibility of a general strike. And he never held back from criticising the so-called ‘violence’ of the striking miners, in conflicts with the police and scab miners, who were a significant, treacherous minority of the workforce, and whose scab neoliberal ‘trade union’, the “Union of Democratic Mineworkers”, played a major role in ultimately defeating the strike.

Political repercussions of the 1984-5 Miners’ Great Strike

The biggest political problem facing the miners and their supporters was the Labour Party and their ‘broad church’ concept, which tied the left to the strikebreaking right wing and rendered them politically impotent to combat Kinnock, the strikebreakers in the TUC, and the UDM, who all backed up the government and the state. To lead a generalised fightback against the neoliberal assault, given the fact that a major chunk of the labour bureaucracy and its growing yuppie-corporate layer supported that programme, it was necessary to have a political alternative that separated from the neoliberals. But the left wing of the Labour Party, the Benns, Skinners, Heffers and Corbyns, were and are bound to the concept of the ‘broad church’ and regarded the idea of splitting Labour with horror. That is still a huge problem today.

The Socialist Labour Party was founded only when Tony Blair abolished the Labour Party’s formal commitment to something resembling socialism, its old Clause 4. Its verbal commitment to a society based on “common ownership” was replaced by a largely anodyne set of platitudes whose real essence was in its praise for “the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition”. However, the formal abolition, though significant, was less so than the connivance of the Labour Party leadership under Kinnock in strategic defeats of the working class, which made such a change of ideology and class outlook possible in the first place. The change was the work of a neoliberal trojan horse within Labour, a new development beyond the traditional politics of the right-wing labour bureaucracy.

The old Labour right wing had been simply an organic product of the trade union bureaucracy’s relationship with large scale industrial employers — the ‘captains of industry’ of British imperialism — in the period when a mass industrial working class was granted concessions of higher living standards from the crumbs of Imperialist plunder more than ever in the days of the British Empire. They therefore had to maintain some relationship with their working-class base, and to be seen to champion them to some extent. The newer, neoliberal right wing does not have such an attachment – they are propelled more by corporate donations in a period when the industrial working class has been massively slimmed down in imperialist countries like Britain by the outsourcing of industrial jobs to lower wage economies in the Global South, and especially East Asia.

Their collaboration is not so much with industrial magnates but rather with financiers and those running service industries, and the volume of donations from financial sharks and services has massively enhanced the power of the Blairites, who really care nothing for industrial workers, as epitomised by Peter Mandelson’s remark that the working class can be safely ignored as it has ‘nowhere to go’ except Labour.

This proved to be untrue, as many such abandoned workers, angry at loss of status as industrial workers who had subliminally understood that they had benefited in part from Britain’s imperial role in the world, went with the imperial nostalgia project of Brexit, UKIP and Boris Johnson, whose real content was “Make Britain Great Again”. An analogue of the slogan of Donald Trump, which much more clearly expressed the mentality of those workers – in Britain, the US, and parts of Western Europe – who bitterly resent their loss of status at the hands of financial capital and the outsourcing of their jobs, and directed that rage in an anti-immigrant, anti-foreigner direction. But ultimately, this consciousness is a desperate and doomed cry of despair. Support for the right-wing populists, who are just as neoliberal and out to enrich the billionaire class as their liberal opponents, is just another way for workers to cut their own throats. Brexit has proven to be a disaster for the workers attracted to it, who have predictably only been shat upon.

We Need a Genuine Working Class Party

Ultimately these are signs that the Labour Party has outlived its function as a party of imperial class compromise, as the working class is losing its imperial privilege, and screaming with pain at the loss. This process is irreversible – Humpty Dumpty cannot be put together again.

So, we are entering a new period of catastrophic change and turmoil in which the need for a new mass party of the working class, capable of programmatic development beyond reformism, to take on the challenges of a working class that has been robbed of its flawed, social-patriotic form of class organisation and consciousness by the decline of imperialism itself, is a burning necessity. The job of Marxists is to point the way forward to the crystallisation of such a party, and Chris Williamson’s initiative with the SLP seems to have the potential to be a major, progressive step in the right direction. This is something that all serious socialists and Marxists must engage with.