By Ian Donovan

The Ukraine war has been many years in the making. Its origins are in the incomplete nature of the counterrevolution that took hold in the USSR, and most centrally Russia, in August 1991. Though it tore apart the USSR and fractured the apparatus whose main function for decades had been to maintain state ownership of the main means of production, it did not result in the dismemberment and destruction of the Russian Federation, the central component of the USSR. Fracturing the state is not the same as obliterating its administrative components. Many important elements survived, albeit in some cases under different titles. But in many cases, they preserved attitudes to property and the various components and classes of Russian society that that were simply customary and had been for many decades, almost as an automatic reflex.

This is the context for the paradox of today’s new Cold War. The driving force of the original Cold War was class antagonism and class struggle: in 1917, driven beyond endurance by the first imperialist World War, the working class of the Russian Empire, supported by the poor peasantry in and out of army uniform, took power as a class and began the task of abolishing capitalism. The revolutionary wave that this was part of, despite convulsing much of Europe, was only victorious in Russia. And that was after fighting off invasion by 13 foreign, mainly imperialist armies – attempted counterrevolution from without in league with the executed Tsar’s ‘White Guard’ general staff. The revolution, in huge, but economically backward Russia, was thus left isolated and prey to a degeneration that caused the proletariat to lose any real control of the state created by the revolution, that consolidated a privileged layer of labour bureaucrats over the working class in power. The material problem is simply that while advanced imperialist capitalism holds sway over the bulk of the globe, an isolated workers revolution, particularly in a backward country, is at a material disadvantage and despite the proletariat being in power, it suffers oppression and material deprivation from the economic siege conditions.

The only solution to this is the world revolution and the overthrow of the bourgeoisie in those oppressing advanced countries, to break the siege. Economic and military siege of a workers’ state is a crucial weapon of imperialism against such states, short of outright military invasion. If the revolution is too long delayed, capitalist restoration begins, in a molecular manner. First with the crystallisation of privileged layers that begin to advocate conciliation with the class enemy, rationalising national isolation into a ‘theory’ that socialism can be built within national borders, abandoning the world revolution as an aim. It continues with the formal dissolution of international organisations, and the gradual, further crystallisation out of the original labour bureaucracy of more overtly bourgeois layers. These agitate politically for ‘market socialism’ and the like, and gradually eat away at the economic planning that the revolution created, seeking a greater economic ‘freedom’, in reality to make money, while exploiting the often-repressive nature of the original labour bureaucracy to demand greater political freedom for bourgeois currents particularly.

This kind of molecular preparation for capitalist restoration took several decades in the USSR. Because of the deep social roots among the masses that the revolution dug, it could only crystallise very slowly. While this was crystallising the USSR, under bureaucratic leadership of this type, fought off the gargantuan imperialist attack of 1941 from Nazi Germany, and then endured the decades-long military and economic blockade of US imperialism, expressed through NATO since 1949. But the health of the world revolution depends on the working class organised politically on an international, i.e., global scale, led by its most class-conscious and clear-thinking political vanguard. Once that is lost, if it is not regained by the conscious action of the masses, capitalist restoration at the hands of the various privileged layers analysed above becomes virtually inevitable.

Thus, there were no politically authoritative forces able to stand up for the USSR in August 1991: only a decrepit remnant of the earlier bureaucratic regime attempted to preserve it against the rampant privateers lined up behind Gorbachev and especially Yeltsin. They were a feeble bunch indeed and when their three-day coup effort failed, the USSR was seemingly rapidly swept away as Yeltsin, the former head of the Moscow Communist Party, took control of Russia and rapidly dissolved the central state, embarking on a massive privatisation exercise and an economic ‘shock treatment’ that forced millions of people into starvation, despair and death as their living standards were rapidly destroyed. Life expectancy fell by around 5 years under Gorbachev and Yeltsin in the early 1990s, something that was only matched in peacetime during the 20th Century by Stalin’s panicked forcible collectivisation of agriculture in the aftermath of the 1929 Kulak revolt (after the bureaucracy, in its own earlier marketising phase, had encouraged the wealthier Soviet peasant layers to “enrich yourselves”). Both events killed several millions. But only the Stalinist famine is exploited by imperialism and its agents to blame ‘communism’; the economic massacre under Yeltsin had the wholehearted approval of the Western bourgeoisies and indeed, Putin is loathed by them precisely for his efforts to reverse a number of Yeltsin’s crimes against the peoples of the former USSR.

The New Cold War: After the Counterrevolution

There is a huge problem with capitalist restoration in countries where for several decades capitalism did not exist, and some element of economic planning took its place. This is clear now, as a new Cold War has begun. In the earlier Cold War, the ideology of ‘Socialism in one country’ led to the perverse situation that giant deformed workers’ states such as the USSR and China were on opposite sides of the geopolitical conflict. From the early 1970s until the collapse of the USSR in 1991, ‘Communist’ China was an ally of US imperialism against the USSR. It fought overtly and covertly against the USSR and its allies in several wars: it invaded Vietnam in 1979 as ‘punishment’ for Vietnam’s 1978 armed overthrow of the most brutally irrational of all the Stalinist regimes – Pol Pot’s ‘Democratic Kampuchea’ (Cambodia). It armed and funded, in alliance with the US and Britain, the Khmer Rouge when they effectively became counterrevolutionary warriors against the pro-Vietnamese Hun Sen government in Cambodia through the 1980s. China funded the counterrevolutionary Islamist mujahedin in Afghanistan though the 1980s in their US-backed war against the USSR and its left nationalist allies of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDPA), whose defeat played an important role in the destruction of the USSR. China funded anti-Soviet, anti-Cuban allies of the apartheid regime in South Africa such as Renamo in Mozambique and UNITA in Angola, against Soviet and Cuban allied post-colonial left populist governments such as FRELIMO (Mozambique) and the MPLA (Angola). This is when the state ideology of China was much more overtly ‘communist’ in colouration, as opposed to today when the whole world knows of the powerful capitalist sector that plays a major role in China.

A form of capitalist restoration took place in China in the early 1990s, from above through a large bourgeois layer, the product of prolonged bureaucratic marketisation beginning around 1979, and proceeding for several decades, gaining sufficient power in the state to absorb key elements of the ruling Communist Party itself. Even Xi Jinping, the current Supreme Leader of the Chinese Communist Party, is part of this billionaire capitalist class which had its genesis within the Stalinist regime and has some markedly different features to the capitalist norm, particularly as seen in the imperialist countries where state power is clearly a tool of corporate power. In China, to a degree, state power overlaps with corporate power in a novel manner that is somewhat unprecedented.

Both Russia and China are thus forms of hybrid societies, where capitalism is very powerful and yet the state power contains much that is left over from the decades when the dominant form of property was state ownership and economic planning. Not socialism, but societies where the forms of property were those corresponding to the rule of the working class and can be said to be part of what should be the transition to socialism. Socialism, or the lower phase of communism, being defined as a society where class-based social antagonisms no longer exist, though the horizon of what Marx called ‘bourgeois right’ has not yet been crossed. Social and economic inequality persists under socialism not between classes as such, but between different sections of the associated producers themselves, simply because social production has not reached the level of abundance for all as to make formal inequality irrelevant. There will be some functions until that point that will require greater material renumeration simply because without that they will not get done. As work becomes more social and rewarding in its own terms it is likely that these will be the most unpleasant and/or dangerous tasks. At a greater level of material-productive and social wealth such considerations will become increasingly irrelevant, and society will cross the horizon of ‘bourgeois right’ to actual communism, the ‘higher stage’. That however is a process that takes time. And neither the USSR nor ‘Red’ China ever achieved even the lower stage of communism (‘socialism’) as defined by Marx, let alone the higher stage.

Limits to Counterrevolution; Further Revolutionary Possibilities

When history rolls backwards though counterrevolution, it rarely manages to do completely. The French revolution that began in 1789 was the greatest of the social revolutions that brought the bourgeoisie to power and overthrew the feudal system of property and production that preceded capitalism in Europe. In terms of its impact in providing the impetus to the overthrow of local forms of feudalism and initially at least, to democracy through Europe, it was one of the greatest events in history. The radical-democratic phase of the revolution under the historic leaders of the Jacobin party, Robespierre, Danton and Saint-Just, where the French aristocracy was basically wiped out by the stern measure of the guillotine, was succeeded by Thermidor, the seizure of power by a more conservative faction, and then the bourgeois Empire of Napoleon Bonaparte. But Napoleon, though his rule decisively ended the radical phase of the revolution at home, nevertheless exported the bourgeois anti-feudal revolution throughout much of Europe, almost all the way to Moscow. Even after the final defeat of Napoleon, the feudal order in Europe was damaged beyond repair. In the succeeding century, all the feudal absolutisms, including Prussia and Tsarist Russia, were forced to introduce capitalist social-revolutionary measures from above to try to prevent them being forced on them from below, as in revolutionary France.

The final defeat of Napoleon in 1815 led to an attempt to restore the old French Bourbon monarchy. Louis XVIII and his successor Charles X were unable to simply restore feudalism and absolutism. The old regime in France was irreparable, and as the history of the 19th Century proved, so was the feudal order in the whole of Europe, which was convulsed by revolution after revolution, from above and below, right through the 19th Century. Out of such bourgeois-revolutionary events the working-class movement itself took shape and began to act as an independent class force in its own right, with bourgeois revolutions interlacing with proletarian class struggles to an increasing extent throughout the 19th Century, reaching an initial high point with the Paris Commune: the first short-lived attempt to create a workers’ state in history. This occurred at the end of the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian war, which was in effect the culmination of the bourgeois revolution (from above) that unified Germany and created it as a capitalist great power.

The culmination of this process took place in Russia, where the bourgeois revolution, centring on the agrarian question and the emancipation of the overwhelmingly peasant population of the pre-capitalist Russian Empire, was carried out by the proletariat in power. That proletariat that had been created by the transplantation of capitalist technique by the Tsarist state in a desperate struggle to compete with the European capitalist-imperialist powers culminating in the First World War.

This interlacing of the bourgeois and proletarian revolutions had fateful consequences for the proletarian revolution in the 20th Century, which still impacts us today. Russia was a state where imperialist monopoly capitalism had been grafted from above upon a still overwhelmingly agrarian country where pre-capitalist relations predominated in the vast countryside. As Trotsky pointed out in Results and Prospects (1906), the only way that the essential tasks of the bourgeois revolution could be carried out was through the seizure of power by the proletariat and the expropriation of the weakest of the great-power bourgeoisies, whose whole existence was bound up with the Tsarist regime. This perspective was carried out in October 1917 by the Bolsheviks, as theorised by Lenin in the April Theses, which replicated the conclusions of Results and Prospects and led directly to the seizure of power by the proletariat, with support from the peasantry who saw the proletariat as its emancipator. But this took place in the context of the imperialist war which convulsed Europe and drove the proletariat to revolt in many countries from the immense suffering of the war.

It was this unique interlacing of the proletarian revolution with the bourgeois in Russian conditions, and the programmatic debates that surrounded how to deal with it, which gave an impetus to the creation of a party that could combine the two sets of revolutionary tasks. This inevitably led to a politics that was considerably different from the debates and political perspectives of the working-class parties in the main protagonists: Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and latterly Italy, Japan and the United States. In these advanced imperialist nations, the social-democratic trends that dominated the proletariat were imperceptibly seduced by the material benefits of imperialism into support for their ‘own’ ruling classes in the war, and internationalists were marginalised by the social imperialists.

In Russia, the overriding necessity to overthrow the infant, weak Russian imperialism in order to settle accounts with Tsarism and its social tyranny over the workers and peasants, once the programmatic complexities of this situation were resolved in 1917, propelled the most radical and revolutionary social democratic/communist party in Europe to the head of the Russian masses to seize working-class state power. This gave a major impetus to the revolution of the European proletariat in a situation where the pro-imperialist backwardness of the proletarian movement in imperialist Europe could not have been more in contrast with the Russian party. The pro-imperialist bourgeois labour parties in all Europe shepherded millions of workers into the inter-imperialist slaughter. In the US there was no real workers party at all. The cleaving of the subjective factor along these lines was a devastating reality, and the failure to overcome it led to the defeat of the European revolutionary wave and the tragic isolation of the Russian revolution in the face of imperialism which managed to remain in the saddle despite the huge upheaval, destruction and carnage of the imperialist war.

In the midst of the revolutionary wave, which occurred as a result of the mass slaughter of the imperialist war despite the betrayal of the social-imperialists, the Communist (Third) International was formed. Its purpose was to defeat the social-imperialists and replace them with genuine mass parties of the working class whose programme was the social revolution on an international scale. Unfortunately, while the revolutionary wave was at its height, despite major gains made in formerly belligerent countries by the communist parties, the social democracy proved too strong to be simply pushed aside by new parties in the immediate sense. The revolutionary wave caused by the huge carnage of the war was victorious only in Russia.

The enormous strength of the revolution enabled the newly-founded Red Army to defeat the counterrevolutionary White Guards between 1918 and 1921. In the process they had to fight off an invasion of 13 mainly imperialist armies, right across the length and breadth of Russia from Europe to the Far East. Yet nowhere else did the young Communist Parties manage to take power. This isolation of the revolution created a new situation previously unknown in history and not fully foreseen by the earlier classical Marxists. The proletariat was in power in a materially backward country, surrounded by more advanced, more productive and ultimately more powerful capitalist-imperialist states. This situation meant that the proletariat, in power for the first time but isolated, was subjected to a new form of oppression by its state power, simply by virtue of the oppressive material circumstances of material deprivation, blockade and encirclement. Over a period of several years, this oppression led to the atrophying of the direct organs of working-class rule, the soviets, and the crystallisation of a privileged labour bureaucracy in the workers’ state. In turn that gave rise, in the next generations as it turned out, to an aspiring capitalist class that inevitably would come to overthrow the workers state if the workers failed to stop it.

Does capitalist restoration happen ‘automatically’?

All this raises some difficult questions about Russia today, about the nature of capitalist restoration, and the prospects for both the anti-imperialist struggle and the world revolution itself, now that capitalism was restored in Russia in the 1990s, was apparently consolidated, and yet imperialism has resumed its war drive against ex-Soviet Russia with a vengeance that resembles the Cold War against the USSR when it was a workers state. Why should this be if capitalist restoration has happened in Russia? What is the meaning of the current geopolitical conflict between Russia, China and the West? And what is the likely outcome, in the event of a defeat of the NATO powers? Is the concept of the Multipolar World, which has been theorised as a possible outcome of Russia’s conflicts with the West, possible or a desirable goal for the international working class?

The essay by Leon Trotsky titled Not a Workers and Not a Bourgeois State, is an important supplement to Trotsky’s major work on the degeneration of the Russian Revolution, The Revolution Betrayed (1936), which defined the USSR under Stalinist rule as a bureaucratically degenerated workers’ state. It was a preliminary response mainly to Max Shachtman, who had begun to question the proletarian nature of the USSR and later would lead a struggle that would split the US Trotskyist movement and cause major divisions in the movement elsewhere.

Not a Workers and Not a Bourgeois State was written in 1937 and began to at least hint at addressing some questions of future development that were slightly beyond the scope of the Revolution Betrayed. It made some important points about the similarity of the relationship of an economically backward and isolated workers state with imperialism, and those of semi-colonial, formally independent, capitalist countries, with the same imperialism. It is worth quoting from Trotsky’s essay because it does cast some light both on the likely path of capitalist restoration in such a situation, and implicitly the likely aftermath:

“The proletariat of the USSR is the ruling class in a backward country where there is still a lack of the most vital necessities of life. The proletariat of the USSR rules in a land consisting of only one-twelfth part of humanity; imperialism rules over the remaining eleven-twelfths. The rule of the proletariat, already maimed by the backwardness and poverty of the country, is doubly and triply deformed under the pressure of world imperialism. The organ of the rule of the proletariat – the state – becomes an organ for pressure from imperialism (diplomacy, army, foreign trade, ideas, and customs). The struggle for domination, considered on a historical scale, is not between the proletariat and the bureaucracy, but between the proletariat and the world bourgeoisie… For the bourgeoisie – fascist as well as democratic – isolated counter-revolutionary exploits … do not suffice; it needs a complete counter-revolution in the relations of property and the opening of the Russian market. So long as this is not the case, the bourgeoisie considers the Soviet state hostile to it. And it is right.

“The internal regime in the colonial and semicolonial countries has a predominantly bourgeois character. But the pressure of foreign imperialism so alters and distorts the economic and political structure of these countries that the national bourgeoisie (even in the politically independent countries of South America) only partly reaches the height of a ruling class. The pressure of imperialism on backward countries does not, it is true, change their basic social character since the oppressor and oppressed represent only different levels of development in one and the same bourgeois society. Nevertheless the difference between England and India, Japan and China, the United States and Mexico is so big that we strictly differentiate between oppressor and oppressed bourgeois countries and we consider it our duty to support the latter against the former. The bourgeoisie of colonial and semi-colonial countries is a semi-ruling, semi-oppressed class.

“The pressure of imperialism on the Soviet Union has as its aim the alteration of the very nature of Soviet society… By this token the rule of the proletariat assumes an abridged, curbed, distorted character. One can with full justification say that the proletariat, ruling in one backward and isolated country, still remains an oppressed class. The source of oppression is world imperialism; the mechanism of transmission of the oppression – the bureaucracy. If in the words ‘a ruling and at the same time an oppressed class’ there is a contradiction, then it flows not from the mistakes of thought but from the contradiction in the very situation in the USSR. It is precisely because of this that we reject the theory of socialism in one country.”

25 Nov 1937, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1937/11/wstate.htm

The juxtaposition of the situation of the semi-colonial capitalist ruling classes, with that of the proletariat in power in a backward and isolated workers state, is highly suggestive of what Trotsky considered likely to happen if the proletariat were to lose power as a class. In a situation where the proletariat even in power was oppressed by imperialist encirclement and backwardness, it is obvious that any bourgeois regime that were to replace it would face the same material conditions, and would likewise be a “semi-ruling, semi-oppressed class”, subject to imperialism. That basic Marxist supposition, implicit in the above passage though not explicitly spelled out is of enormous importance today in understanding not only Russia but also China, and likely other former workers states such as Vietnam which have (so far) not played a major role in the current developing new Cold War between imperialism and the giant former bureaucratically ruled workers states.

What we are actually faced with is the aftermath of the counterrevolution in the USSR. Trotsky also had some useful observations about the course of counterrevolution, actual and likely, in the context of both the French (bourgeois) and Russian (proletarian) revolutions in an earlier (1935) piece, The Workers State, Thermidor and Bonapartism. Talking directly about the French revolution, he wrote:

“After the profound democratic revolution, which liberates the peasants from serfdom and gives them land, the feudal counterrevolution is generally impossible. The overthrown monarchy may reestablish itself in power and surround itself with medieval phantoms. But it is already powerless to reestablish the economy of feudalism. Once liberated from the fetters of feudalism, bourgeois relations develop automatically. They can be checked by no external force; they must themselves dig their own grave, having previously created their own gravedigger. “

https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1935/02/ws-therm-bon.htm

He contrasts that with what would be likely in the event of the collapse of the Stalinist regime and the Russian revolution with it:

“It is altogether otherwise with the development of socialist relations. The proletarian revolution not only frees the productive forces from the fetters of private ownership but also transfers them to the direct disposal of the state that it itself creates. While the bourgeois state, after the revolution, confines itself to a police role, leaving the market to its own laws, the workers’ state assumes the direct role of economist and organizer. The replacement of one political regime by another exerts only an indirect and superficial influence upon market economy. On the contrary, the replacement of a workers’ government by a bourgeois or petty-bourgeois government would inevitably lead to the liquidation of the planned beginnings and, subsequently, to the restoration of private property. In contradistinction to capitalism, socialism is built not automatically but consciously…”

“October 1917 completed the democratic revolution and initiated the socialist revolution. No force in the world can turn back the agrarian-democratic overturn in Russia; in this we have a complete analogy with the Jacobin revolution. But a kolkhoz overturn is a threat that retains its full force, and with it is threatened the nationalization of the means of production. Political counterrevolution, even were it to recede back to the Romanov dynasty, could not reestablish feudal ownership of land. But the restoration to power of a Menshevik and Social Revolutionary bloc would suffice to obliterate the socialist construction.”

ibid

But what has actually happened is more complex. We have had something roughly akin to “the replacement of a workers’ government by a bourgeois or petty-bourgeois government … ” and “….the restoration of private property” in Russia since the 1991 collapse of the USSR. In China, we have had policies carried out for decades – abolition of Kolkhoz (collective farming) and the naked encouragement of capitalist enrichment both rural and urban — under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party – that Trotsky considered would lead to the rapid collapse of the Soviet Union into a kulak-led counterrevolution in the late 1920s. By the standards of the struggle of the Left Opposition against the Stalin-Bukharin bloc and its Neo-NEP – it is inconceivable that the regime of the Chinese Communist Party, with its numerous billionaire capitalists whose influence penetrates to the very top of the CCP regime, could be described today as a workers’ state. It is evident that China today is something fundamentally different from the old CCP regime under Mao, and that state power today is used to defend and promote the capitalist development of China, not to suppress it.

And yet far from stabilising world capitalism under the rule of the imperialist bourgeoisie, we now have a considerable level of unity in defensive struggle of the two giant former workers states of Russia and China, against US/led NATO imperialism, which grows more and more hysterical every day. It is worth recalling Trotsky’s remarks above that:

For the bourgeoisie … isolated counter-revolutionary exploits … do not suffice; it needs a complete counter-revolution in the relations of property and the opening of the Russian market. So long as this is not the case, the bourgeoisie considers the Soviet state hostile to it ….”

This appears to have been only part of the story. Just as with anticipations and theorisations by Marxists of what might happen if a workers revolution triumphed in a backward country, the theorisations of what would happen if such revolutions were subsequently defeated, by even the best Marxist theoreticians, including most notably Trotsky himself, have proven inadequate for the task. “Theory is grey, but green is the tree of life” is an old saying, but that does not mean that anyone should dismiss Marxist theory in some cavalier and philistine fashion. Theory is a guide to action. But such is the profundity and complexity of world-historic events, when they emerge, that they invariably cause a crisis in existing theories, a need to re-examine, correct and deepen existing theory to provide an updated guide to action for a new period.

It does appear that Trotsky was correct to say, of the bourgeois revolution, that “once liberated from the fetters of feudalism, bourgeois relations develop automatically” (see earlier). However, that automaticity does not transfer mechanically to a situation where it is not feudalism that is overthrown by capitalism, but a workers’ state, however degenerated, based on socialised property.

The restoration “to power” of something rather similar to “a Menshevik and Social Revolutionary bloc” took place in the 1990s in a number of bureaucratically ruled workers states, but it does not seem to have been simply able to completely “obliterate the socialist construction”. When degenerated and deformed workers states have been overthrown by pro-capitalist forces, it has not been the case, unlike with feudalism, that “bourgeois relations develop automatically”. What we have in fact seen is that the kind of “bourgeois relations” that have developed have been highly problematic and have in fact given rise to hybrid forms of society that the imperialist bourgeoisie does not have confidence in at all. States have emerged that still contain enough modifications of those features of capitalism as a system that the imperialists consider vital and non-negotiable, that the same imperialists fear that capitalism has not been sustainably restored at all, and these societies could flip back to some sort of socialist construction as easily as 19th Century France did to bourgeois-revolutionary upheavals after the defeat of Napoleon, with its supplementary revolutions in 1830, 1848 – which convulsed the whole of Europe – and 1871 – which gave rise to the Paris Commune, the first attempt in history to create a workers state.

‘Deviant’ Counterrevolutions and Imperialist Hysteria

What seems to have come into existence in those workers states where indigenous social revolutions were once victorious and defeated many decades later, are hybrid states where capitalist relations are modified in significant ways, and those states do not function either as copies of the imperialist states, or as semi-colonial vassal states. Neither Russia nor China fit into either category. As opposed to passively produced ‘satellite states’ like most in East Europe, which have generally become satellites/vassals of Western imperialism.

The deadly imperialist shock treatment in Russia under Yeltsin in the 1990s produced such a huge popular backlash that within the state machine itself, a nemesis was generated, personified by Putin, that rolled back many of the attacks, and though it did not restore the status quo ante, produced a variant of a social-democratic ‘mixed economy’ with considerable concessions to the welfare of the masses, whose genesis is arguably pretty unique. In a ‘pure’ capitalist state, it would take the threat of revolution itself to produce such concessions which would always be under threat. In post-Soviet Russia, the state apparatus itself, heavily marked by its origin in a workers’ state, responded to mass popular sentiment without such upheavals.

Something analogous seems to have happened in China, but with some important differences also. One key difference being that in China initially the capitalist-restorationist programme was carried out from above, without the kind of all out economic war on, and carnage of, the working-class population that happened in the former USSR. Another key difference is that China actually benefitted from Western neoliberalism in that it became a key repository of ‘outsourcing’ – job migration — from Western imperialist countries, whose capitalist rulers saw China’s cheap but highly-educated working class in the context of apparent capitalist restoration as an opportunity for a massively enhanced rate of profit relative to what was possible in the imperialist countries themselves. China was not the only country that acted as the recipient of such outsourcing, but its state apparatus, which also had its origin in an era of state economic planning, was able to make use of it to embark on its own massive industrialisation. As a result, China has become today’s “workshop of the world” in a manner reminiscent of Britain during the 19th Century Industrial Revolution, but on far vaster scale.

The real driving force of Western Russophobia is not the supposed ‘authoritarianism’ of Russia’s political regime, but anger at the political clout that the Russian masses still hold within what used to be their state. Hatred of the Russian people themselves is a key element of today’s Western Russophobia, which resembles Nazi hatred of the Jews for their supposedly inherent ‘Bolshevism’. Likewise, today’s Sinophobia is the rage of imperialism at the seemingly unexpected industrial development of China. This was not supposed to happen – China was supposed to be a mere source of profit, not a major industrial adversary able to threaten US hegemony. And Russia and China together are an even more potent countervailing force to the hegemony of the imperialist powers which has persisted since the late 19th Century at least.

So, what is at the root of this paradox? One hint of an answer can be found in a formulation in Engels’ 1880 work Socialism Utopian and Scientific, where he makes the following point about the tendency of capitalism towards the generation of trusts and monopolies:

“In the trusts, freedom of competition changes into its very opposite — into monopoly; and the production without any definite plan of capitalistic society capitulates to the production upon a definite plan of the invading socialistic society. Certainly, this is so far still to the benefit and advantage of the capitalists. But, in this case, the exploitation is so palpable, that it must break down. No nation will put up with production conducted by trusts, with so barefaced an exploitation of the community by a small band of dividend-mongers.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/ch03.htm, emphasis added

This formulation, about the ‘invading socialistic society”, stems from the basic idea of Marxism, held in common by Marx and Engels, that “socialism” or “communism” which they considered as two manifestations of the same thing (‘lower’ and ‘higher’) represented a superior mode of production to capitalism:

“Development of the productive forces of social labour is the historic task and justification of capital. This is just the way in which it unconsciously creates the material requirements of a higher mode of production.”

Capital, Vol. 3, Moscow, 1966, Chap. 15, p. 259

Much of Trotsky’s polemic against the Stalinists in the 20s and 30s was against the theory of socialism in one country, the notion that it was possible to build a complete socialist mode of production in a society qualitatively more backward than the far stronger capitalist-imperialist powers that encircled it. That critique retains its full relevance and potency. But then again, Trotsky also noted that despite this, the reactionary course of the Stalinist regime “… has not yet touched the economic foundations of the state created by the revolution which, despite all the deformation and distortion, assure an unprecedented development of the productive forces.” (Once Again: The USSR and Its Defence, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1937/11/ussr.htm)

Engels considered that the socialist mode of production, which was completely in the future in 1880 when he wrote Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, had the ability to ‘invade’ contemporary capitalism, and as a kind of unconscious expression of the historical process, affect the development of the same capitalism to (in some ways) anticipate future developments that would come to fruition under a higher mode of production. This is only an expression of the basic Marxist concept that Socialism: Utopian and Scientific expresses — the objective tendency of social development toward socialism:

“The new productive forces have already outgrown the capitalistic mode of using them. And this conflict between productive forces and modes of production is not a conflict engendered in the mind of man, like that between original sin and divine justice. It exists, in fact, objectively, outside us, independently of the will and actions even of the men that have brought it on. Modern Socialism is nothing but the reflex, in thought, of this conflict in fact…”

Engels op-cit

The point being that the process of capitalist restoration, the destruction of a long-established workers state, cannot be ‘automatic’ in the manner in which capitalism is able to do away with feudalism. The existence of a workers’ state, however deformed or degenerated, means that that state has already begun the transition to a higher mode of production, communism. Even if the transition is blocked by social backwardness, imperialist encirclement and the monopoly of power of a bureaucracy that opposes and attempts to sabotage the world revolution and thereby the completion of the transition, the transition has begun. The train has left the station, even if it is stalled only a few hundred yards down a track that is many miles long. It is extremely heavy, and still very difficult to simply drag back to its starting point and beyond.

So, what we have in both Russia and China are forms of society where capitalism appears to have been restored, and yet the “invading socialist society”, has modified and blocked the transition backwards. The previous regimes began some kind of transition to the communist mode of production, even though it was sabotaged and blocked by those same regimes, and the existence of those partial gains have proven much more difficult to destroy than previously anticipated, including by the Trotskyist movement in their fragmentary attempts to address what would happen if capitalism were to be restored. This substantially modifies the capitalism of Russia and China and has produced anomalous hybrids, which are not imperialist themselves (why would they be, the former workers’ states did not operate on a capitalist basis at all, let alone a predatory, monopoly capitalist basis?).

The hybrids can be of heterogenous types, depending on the specifics of their history and origins, and there is no pre-ordained ideological banner which is imperative for their ruling political trends to necessarily uphold. Though China is ruled by the Communist Party, whose ideology is a capitalist bastardisation of what was Stalinist ‘Communism’ but really isn’t anymore, Russia is ruled by the centre-right bourgeois (sui-generis) Orthodox Christian President Vladimir Putin, leader of the hegemonic and highly popular ‘United Russia’ party whose authority stems largely from economic programme and practice, which have tangibly and arguably hugely benefited most Russians since the end of Yeltsin’s carnage.

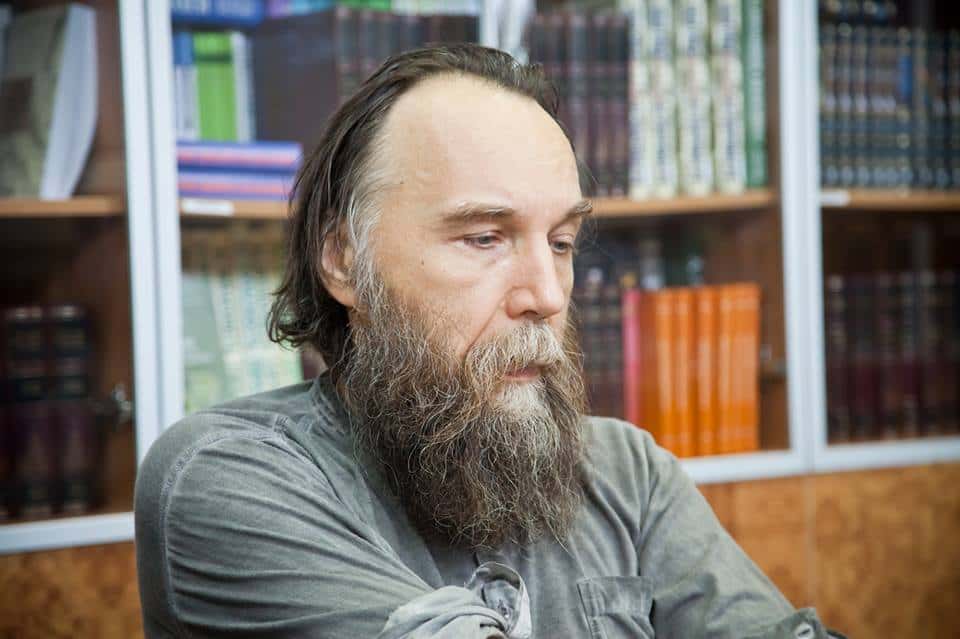

Putin is a kind of a mild Bonapartist who balances between forces to his left and to his right. To his left is the main opposition, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF), the former Stalinist Party which has many subjective communists among its base but has not determined as yet what it really stands for. To his right is the broadly ‘Eurasian’ trend most prominently led by the philosopher Alexander Dugin, who many in the West dub as a fascist, a Russian nationalist, a great Russian imperialist, etc. This kind of demonisation was used to justify the August 2022 murder of his daughter, political scientist and journalist Dariya Dugina, probably by Ukrainian Nazi terrorists in partnership with Western intelligence agencies, who are engaged in an ongoing campaign of murder and terrorism against public supporters of Russia’s resistance to the West’s proxy war in Ukraine. Their objective was Dugin himself, not his daughter, but they got it wrong.

A close examination of Dugin’s politics reveals that he is opposed to ethnic nationalism, rejects the whole concept of the nation-state explicitly in theory, and actually looking back at history has managed to construct an ‘Orthodox Christian’ rationale for critical support for Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolshevik Party forces in the 1918-21 Civil War against the mainly Christian Orthodox White Guard forces, whom he very perceptively dismisses as tools of Anglo-American imperialism and therefore enslavers of the Russian people (as elaborated in his 1997 work Foundations of Geopolitics). Thus Dugin, the ‘right-wing’ pressure on Putin, is revealed as a hybrid, and a perfect illustrator of the hybrid nature of the state. A supposed ‘fascist’ who argues for critical support for Bolshevism, whereas actual fascists, like Hitler and Mussolini, were driven by the most virulent hatred for Bolshevism.

Dugin is demonised as some sort of Nazi by the Western powers who support Nazis, which goes hand-in-hand with depictions of Putin as a Hitler figure in the reactionary media. Dugin is supposed to be “Putin’s Brain” in this preposterous alleged Hitler-like endeavour. Anyone would think that Dugin therefore is an advocate of Russian world domination, or something. But no: Dugin is also the author of a 2021 book titled ‘The Theory of the Multipolar World’ which far from advocating anyone’s world domination, calls for a voluntary collaboration of a variety of ‘civilisations’ to ensure no one is able to exercise world domination (or ‘full spectrum dominance’ as the US neocons put it – they really do want world hegemony/domination). Dugin rejects nation states, and he has a schema where these ‘civilisations’ – one centred around Orthodox Christian Russia – are part of this collaborative multipolarity. He does indeed want a strengthened and more broadly influential Russian-centred ‘civilisation’ to play an influential role in the world, and some of his ideas and proposals are deeply at odds with Marxism and the perspective of human liberation, but this is very far from the Russophobic depiction. He is subjectively hostile to Western imperialism, though in a way rather similar (mutatis mutandis) to the sentiments that drive militant Shia clerics in Iran or Lebanon, not anything resembling Nazism at all. Dugin’s politics and literature require a level of analysis that is beyond the scope of this article and will have to wait. This only scratches the surface.

These hybrid post-Stalinist states have proven capable, because of the enormous productive gains (and military developments) that were made without capitalism, of defying imperialist capitalism far more effectively than any rebellious semi-colonies. Instead, as the imperialists have declared a cautious but accelerating new Cold War against them (with ‘hot’ elements, like Ukraine) they have proven capable of leading semi-colonial, capitalist countries, long forced into dependence and vassalage to the imperialists, in revolt against imperialist hegemony.

Revolt of the Victims of Today’s Imperialism

We have effectively a revolt by numerous semi-colonies against US imperialist hegemony of an economic and political nature, under the banner of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and also the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). These bodies overlap, though the SCO is specifically Eurasian, whereas BRICS is worldwide. Despite the imperialist war drive and economic sanctions against Russia, and the threat of ‘sanctions’ against any country outside the imperialist ‘club’ who does not join in the sanctions. 20 countries have applied to join BRICS, including Argentina, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iran, Indonesia, and many more. BRICS before their joining encompassed 40% of humanity … the accession of the hopeful newcomers would undoubtedly encompass a majority.

BRICS has something of the flavour of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) led by Nkrumah, Nasser, Nehru, Sukharno, etc. along with the dissident liberal-Stalinist Tito in the early post-war period. Although it still formally exists, its influence is very diminished. The NAM aimed to manoeuvre between the US and the Soviet bloc in the Cold War, understanding that most semi-colonial countries and their bourgeoisies had major divergences of interest with both. But now there is much more commonality between such countries and Russia and China, most semi-colonial bourgeois states see them as kindred spirits, but more powerful, and having shifted the relationship of forces against imperialist domination in a way that is fairly unproblematic for such bourgeois regimes. Few take China’s verbal ‘communism’ seriously at all and Russia has no such ideological obstacle even formally. So, the main agency of challenge to US hegemony in favour of the multipolar world is BRICS.

There have been some startling indications of changes in the world to the detriment of US imperialist hegemony that have been brought to a head by the Ukraine war. De-dollarisation, the jettisoning of the US Dollar as the habitual currency of which international transactions are made – previously almost irrespective of who is trading with who – has become a major movement. This is a threat to US financial stability and military power, as the US has been for many decades been able to write virtually a blank check for its military based on the earnings received from the dollar being pretty much the dominant currency for international trade. Its worldwide network of military bases is financed through this mechanism. The rise of the Russia-China bloc threatens all that, as BRICS have created their own development bank and are also discussing the creation of a new agreed currency for international transactions.

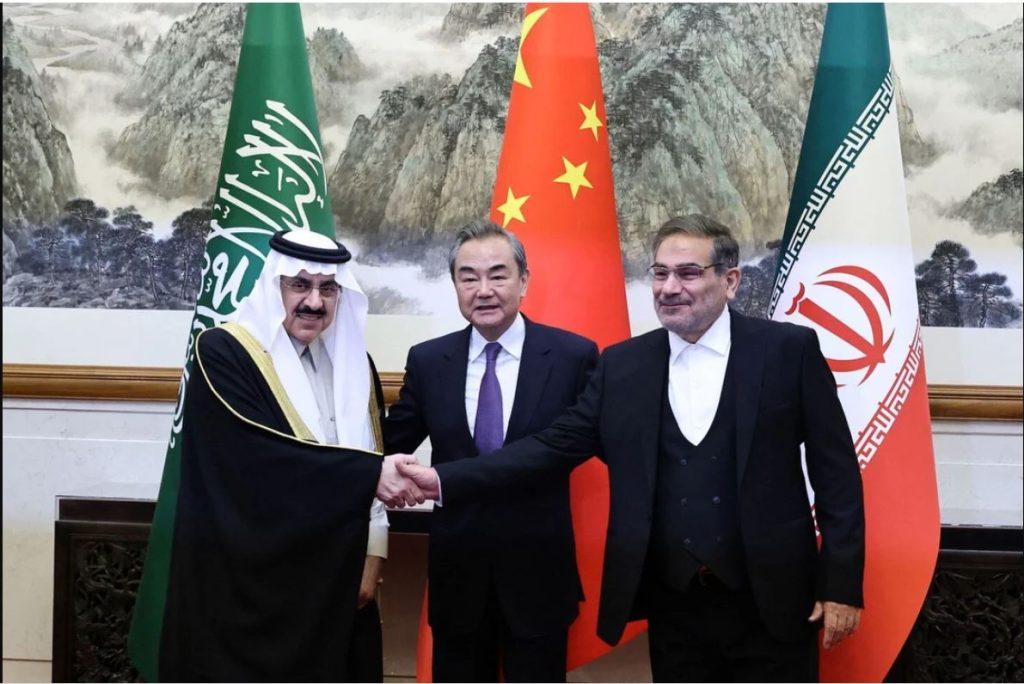

One startling index of how things are changing is in the Middle East. In deals brokered by Chinese diplomacy, Saudi Arabia and Iran, who have been in a state of bitter antagonism for many years, as most sharply expressed in the war in Yemen, have restored full diplomatic relations, and the Yemen war is apparently winding down. Syria, whose Assad government the US and its allies tried to overthrow in a similar manner to Libya and were stopped from doing so by Syria being given armed backing by Russia, has now been restored to membership of the Arab League after former US clients dropped their antagonism. The US is on the defensive in the Middle East and China has also made demands for a settlement of the Israel-Palestine question, which is certain to prove much more difficult because of the problem of the overlap of Israel’s ruling class with that of Western countries – the material basis of the very powerful Israel lobby.

But the broader question is whether this concept of a multipolar world is somehow an antidote to imperialist capitalism. And the answer has to be one of deep scepticism towards that. Capitalist development has created an exclusive club of monopoly capitalist powers that basically have enriched themselves massively at the expense of the bulk of the world’s population for a century and a half, with a couple of centuries of preparation before that through mercantilism and primitive accumulation of wealth through such means as a revived chattel slavery on an industrial scale, which was only done away with when it became an obstacle to capitalist development. The problem is that a multi-polar world does not do away with those powers, who will inevitably fight back in some way, either jointly or separately. US hegemony is not the only possible form, and the NATO that is the current expression of imperialist domination. It is worth recalling that between the two world wars there was no undisputed imperialist hegemon – that role was contested between Germany, Britain and the United States and the resulting armed dispute plunged the whole world into war. Such a development in the future could destroy humanity itself.

Imperialism is coherent in its socio-economic objectives, even though it can be thrown into disarray by unexpected challenges from other forces. It will not just disappear into a peaceful ‘multipolar world’. The lion will not lie down meekly with its victims for the greater good – for imperialism the majority of humanity are just fodder for exploitation. The problem that they face is a historical crisis – the capitalist system itself declined through the decline in profit rates in the advanced countries to the point that only outsourcing, overseas cheap labour schemes and industrial-scale financial frauds such as Credit Default Swaps etc. could keep up the rate of profit. That is an inherent contradiction in capitalism itself, as Marx pointed out, and affects all capitalism.

The creation of hybrid capitalist/post-capitalist states like Russia and China, a new form of anomalous non-imperialist capitalism that uses state power to offset the most irrational drives of capital, cannot simply be reproduced. Because it takes the creation of a fundamentally flawed workers state, and then its ruin, to bring such a hybrid into being. And another paradox is that it was the overall strength of the existing imperialist states throughout nearly a century and a half that allowed those same imperialisms to act as an exclusive club and block the development of other capitalist powers into imperialist competitors. So, the only new imperialism that was created in the late 20th Century, which did not emerge organically, but was transplanted, was Israel.

There is a possibility that a strategic defeat for existing imperialisms by these hybrid states could have the effect of creating the political and economic space for new imperialist states to crystallise. The most developed semi-colonial states that are jumping on the bandwagon of BRICS may well be provided with the means of economic development to the point that they are able to exploit less powerful semi-colonial countries, and thus begin to behave as new imperialisms themselves. That seems a possibility for instance with India and Indonesia, whose rapid economic development is not restricted by any kind of hybrid state inherited from a previous social revolution.

And overarching this is the question of the palpable destruction of the world’s climate by capitalism with its fossil fuel industry, a problem that can only be resolved by an end to the profit motive as the force driving economic development, and its replacement with economic planning on a global level to make it possible to transform the world’s energy generation to use means that do not destroy the environment for human habitation. Which is currently happening, and not slowly.

Even if the wildest dreams of the theorists of the multipolar world are realised, and a new world mechanism of voluntary collaboration between discrete chunks of the planet is able to bring a sustained new rationality to international relations, that will not solve the fundamental problem: humanity will still be afflicted with the contradictions of capitalism. All the different ‘civilisations’ in Alexander Dugin’s ‘multipolar world’ schema are basically built on some form of capitalism, irrespective of ‘culture’, and thus are subject to some or all of these contradictions, even abstractly without the role of the established imperialist capitalist states. The idea that such a configuration could overcome capitalism’s tendency to war and barbarism is indeed utopian reformism.

This contradictory moment in the history of capitalism would never have been possible without the 1917 workers’ and peasants’ socialist revolution in Russia, and then the secondary, derivative but enormous revolution of Mao’s peasant armies in China leading to 1949. It will prove to be fleeting unless the problem pointed out earlier, of the domination of the workers movement particularly in the advanced countries by social-imperialists, at war with those who stand on the revolutionary outlook of the Bolsheviks, is resolved. To resolve it a new Communist International has to be created, with deep roots in the imperialist countries themselves, able to stand up to imperialist pressure and prevail. A successor to the previous attempts of the Third and Fourth Internationals that for diverse reasons have fallen by the wayside. A new regroupment of communists is therefore necessary to create such a movement, otherwise the historic opportunity of this major crisis of imperialism could be lost.