This is the presentation (with some edits and corrections) that was given by a Consistent Democrats speaker at our educational on 21st July. The recording of the meeting is also available as a podcast, and can be found here.

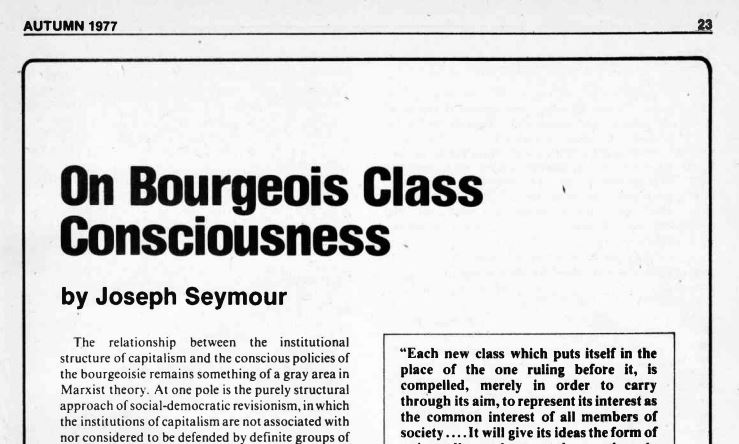

The essay that this educational is about was a seemingly abstract commentary made by Joseph Seymour, key intellectual figure of the Spartacist League of the United States in the mid-1970s. The old Spartacists were a contradictory political trend with roots in both of the two major trends in the US that emerged from the Trotskyist movement in Trotsky’s day.

The US Trotskyist movement had been founded in the late 1920s by three prominent members of the US Communist Party: James P Cannon, Martin Abern and Max Shachtman. The US Left Opposition and its successors – most notably the US SWP – always worked very closely with Trotsky and carried out many of the tactics of the Trotskyist movement in the years before the founding of the Fourth International in 1938. It did serious work in the trade unions. In 1934, its trade union militants led the Teamsters’ (truckers) strike in Minneapolis, one of three major strikes that year led by Communist groups in the period of revival of the workers movement after the worst of the Great Depression. And it carried out a short-term entry into the Socialist Party in 1936-7, which enabled it to fuse with a layer of younger militants.

In some ways, the SWP – a thousand or so people – became the leading party of the Fourth International when it was founded in 1938. Their geographical closeness to Mexico was an advantage in collaborating with Trotsky in his final exile. They were also subjected to the pressures which the whole of the movement was subjected. Because of the relatively open situation they lived in, the issues were fought out in the open.

The Stalin-Hitler pact in 1939 caused splits in the Trotskyist movement. A wave of hysterical Stalinophobia, that equated Stalin’s regime with Hitler’s, swept the labour movement in the imperialist countries. In the US, a faction led by Shachtman, Abern and James Burnham (an academic figure) was formed, which abandoned defence of the Soviet Union against imperialism. By the end of the dispute in 1940 Shachtman had developed the theory of bureaucratic collectivism, the USSR as a new class society, neither capitalist nor socialist, but worse than capitalism.

Cannon, and the core trade union cadre of the SWP, joined with Trotsky to defend the USSR as a degenerated workers’ state. These issues were fought out comprehensively. Two important books are availble on this: Trotsky’s In Defence of Marxism, and Cannon’s The Struggle for a Proletarian Party.

In 1940 Trotsky was assassinated. The Trotskyist movement faced WWII without his insights. The complex sequence of events in WWII led to the defeat of Nazi Germany and its allies, Italy and Japan, primarily by the USSR in alliance with the US, with Britain and France in tow. The situation after the war was a mess. The Stalinists defeated Nazi Germany, but also made sure that the working class as an independent class did not come to power anywhere. Wherever the working class threatened to come to power directly, the Stalinists united with imperialism to crush it. Most notably in Europe, in France, Italy and Greece in Europe, and in Vietnam with the Saigon workers insurrection in 1945.

But there was also the unstable phenomenon of the creation of deformed workers states, in East Europe, China, and elsewhere. The Trotskyist movement was disoriented by the creation of these states without the conscious action of the working class. The imperialists were implacably hostile to the USSR’s victory and the new deformed workers’ states and set up NATO as an aggressive instrument to fight them. The Cold War ensued.

After the war, without Trotsky’s guidance, the Trotskyist movement partly capitulated to Stalinism, and many began to hail bureaucratic Stalinist leaders as revolutionaries who would lead the world revolution. Others followed in the footsteps of Shachtman and capitulated to imperialism. There was little coherent understanding of what had happened. There were a lot of very complex and confused debates. The Sparts represent one fragment of these debates. They got possibly the trickiest problem right, that of Cuba. Which ought to have laid the basis for resolving all these problems. But it was not to be.

Fidel Castro and his guerrilla movement came to power in 1959 and overthrew a classic US-backed neocolonial tyranny. Then they proceeded to nationalise virtually the entire Cuban economy to preserve themselves from being overthrown by the Cuban bourgeoisie who simply worked with US imperialism. Some Trotskyists, including the ageing US SWP cadre, hailed Castro as an unconscious Marxist and world revolutionary. Others denied that there had been a revolution in Cuba at all.

The Spartacists got this right and understood that while Cuba was a workers’ state and had expropriated capital, it was a deformed workers state that needed a supplementary political revolution to bring the working class to genuine political power. Castro had come to power at the head of a movement that was not initially communist even in name. He was a liberal, who emerged from the Orthodoxo Party. Yet in power, his July 26 movement changed its ideology to match what it had done and joined the Soviet bloc. Their understanding of Cuba clarified what a deformed workers state was.

Such states had been generally created by communist movements that had abandoned the working class, based instead on an oppressed peasantry, and that these parties had become petty-bourgeois nationalist parties. When the working class was politically paralysed and under extreme conditions of imperialist oppression, such movements proved capable of overthrowing capitalism and creating such workers’ states, but with a fundamental weakness, that was later to destroy most of them. I.e, an anti-working class, bureaucratic regime, committed to socialism in one country, similar to the USSR under Stalin and since. In Cuba, however, unlike all the other examples where such states were created independently of simple conquest by the USSR, the movement that carried this out was not even formally communist before the revolution. This was clarifying as to what was really involved in the others, such as China, Yugoslavia, etc. This was a very perceptive and thoughtful analysis. No one else developed it at the time.

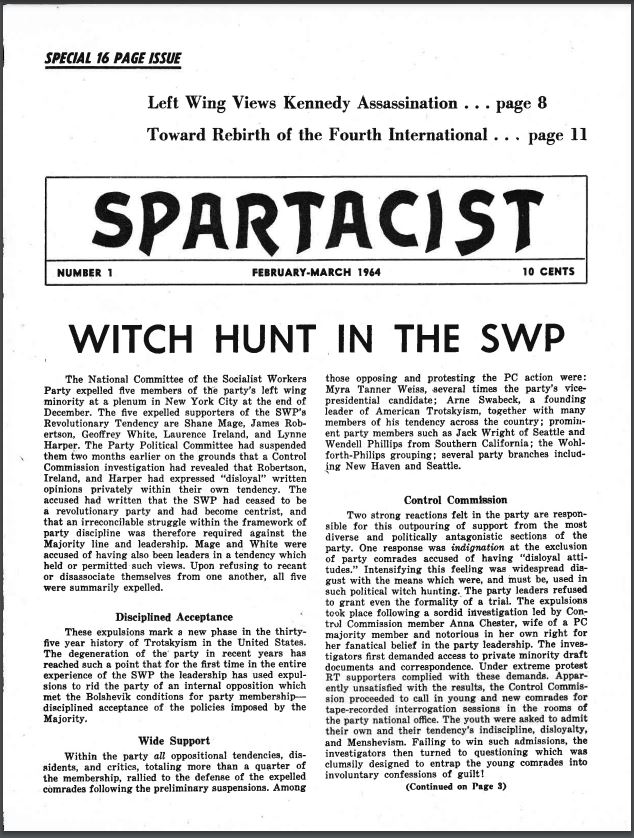

The Spartacists in the decades to come used this to argue that they were the continuity of Cannon’s SWP in its best period, created under Trotsky’s guidance, and therefore the only real Trotskyists in the world. This had some apparently credibility in their earlier period, but this was incorrect, a conceit based on a partial understanding, that slowly drove them mad. It was wrong, because they were rooted in both strands of the pre-war movement. The founders of the Sparts, particularly Roberston and also Wolhforth, who played the key role in the creation of this trend, came from Shachtman’s anti-Soviet Workers Party, not the SWP.

They joined the ageing, rightward-moving SWP in the mid-1950s, on the basis of being won to orthodox Trotskyism on the Russian question, and later were thrown out for being right about Cuba. But Roberston, who became the leading figure, though he had broken from Shachtman over the Russian question, had not questioned another aspect of Shachtman’s politics: his left-Zionism. As part of their right-wing evolution at the beginning of the Cold war, the Shactmanites had supported the creation of Israel. That was another political strand.

In the coming decades the Sparts produced orthodox material on the Russian question, given weight by their correct understanding of Cuba, for instance their opposition to Solidarnosc in the 1980s. But this correct politics was mixed with material on Israel/Palestine that in the earlier period sided with Israel. They also copied that approach and tried to apply it to the Irish question from the late 1960s. Originally, they were (in a strange way) pro-Unionist in Ireland. In 1973, trying to address the Irish struggle that had raged since 1968, they called for a independent Ulster, supposedly as part of a ‘socialist’ programme to unite Ireland! Later they modified their positions to be effectively neutral in these national struggles. Calling on Arab and Jewish workers in Palestine, or Nationalist and Unionist workers in the North of Ireland, to abandon their national struggles and unite. Not much of an improvement. They were a perplexing phenomenon, because they were partly right, and partly severely wrong. Which is very damaging, as an old saying has it, a half-truth is more damaging than an outright lie. This contradiction gave rise to an organisation with a strange and damaging way of working, a reflection of their political contradictions.

But they were sometimes capable of great insight. Seymour’s article is a startling example. Seymour’s article steers completely clear of any superficially complex colonial questions. It leaves that aspect of Spartacist politics completely alone. That is its strength. Instead, it deals with the problem of how the class consciousness of the imperialist bourgeoisie works and attacks some misconceptions of this that are common on the left. He contrasts different concepts of left reformism about how capitalist society works. The structural concept and the conspiracy concept.

For some reformists capitalism is purely a matter of a structure. All you have to do is change the structure and society will improve incrementally. There is no sense in this that there are real material interests that dictate these structures, i.e. property relations that reflect the interests of a specific layer – the capitalist ruling class.

And there is the view that capitalism itself works through a series of conspiracies. The job of socialists is therefore to combat and expose the conspiracies. This may seem very radical, but it is flawed, and can also lead to a pessimistic view. There are a lot of those concepts around now, both on the right and on the left, in different forms.

You hear those who attach great importance to the World Economic Forum, who are seen as so advanced and the real rulers of the planet, somewhat different to the ruling class itself. An earlier example is the whole series of similar theories about the Bilderberg group. The ‘Great Reset’ theory is linked to the theories about the WEF and presupposes some demonic scheme – the leftist variant being to destroy all previous gains of the working-class movement. The right-wing variant of this has theories of the ‘replacement’ of the population of the imperialist countries with immigrants. Both of these found common ground in various theories about the Covid pandemic, that this was part of some sinister scheme to do one or the other of these things, according to the particular leaning of the theorists. This blurred the difference between left and right. It has to be said that as their organisation collapsed around 2020, and then created a new leadership, the Spartacists seemed to go through some strange political-psychological process where they seemed lost in paranoia about the Covid pandemic.

But as Seymour points out, the bourgeoisie does not have the level of coherence that such theories imply. These various think-tanks are partial. They are the brainchild of various bourgeois milieux who are fallible and capable of misunderstanding reality as much as any other group of bourgeois. If your world view is that the class struggle depends on who can organise the most effective conspiracies, it is not a huge step from this to the view that the bourgeoisie is too clever and capable of organising conspiracies to be overthrown. That leads by another route to submission to bourgeois authority, and instead attempts to convince the bourgeoisie to mend their ways. To another form of reformism, in other words.

Monopoly capitalism is getting more and more concentrated. And firms connected by neoliberalism, venture capital and banking are getting more and more powerful. Examples do exist of a worldview where capitalist society can jump over the law of value. Modern Monetary Theory is such a position. The idea that ‘fiat’ currencies are almost infinitely expandable, provided they can be kept essentially separate from other currencies.

The bourgeoisie are not conspiratorialists who run the world according to a plan. They are not Marxists in reverse, and Seymour is at pains to emphasise this. Their real aim is to realise surplus value, or to put it more simply, to make profits. They are quite capable of forming factions on a large or small scale to do each other down, or to crush or even in extremis to slaughter each other, via ‘their’ workers, in inter-imperialist wars, if they feel it necessary from their own particularist standpoint. Their ideology is not Marxism looked at from the other end of the telescope. They do not apply reverse class struggle concepts in any scientific manner to the class struggle from their side. Individuals may boast of doing such things, but bourgeois class-war tactics are empirical, and may undermine their own interests in the future.

For instance, Thatcher’s destruction of heavy industry in Britain was straightforwardly done to undermine what was in the 1970s the strongest trade union movement in Europe. It succeeded. But in doing so, it accelerated Britain’s decline as an imperialist power enormously. Something similar happened in the US. Much productive capacity was outsourced to China and other low wage countries to cut down on labour costs. China gained a lot from that. Now all factions of the US bourgeoisie regard China as a major threat. This is not smart.

The bourgeoisie persists in this behaviour, it cannot do otherwise, it is how it thinks. Social being determines social consciousness. Various ex-Marxist ideologues have chided the bourgeoisie with such short-sightedness. James Burnham, after he broke from the US SWP and moved rapidly to the right from Marxism to right-wing cold war militarism, wrote a book called The Suicide of the West which as Seymour said was:

“…designed to prove that the dominant political attitudes of the American ruling class were optimistically false.”

He was ignored, and in part ridiculed. The bourgeoisie is episodically capable of class unity when confronted with a potent threat from the working class, but that rarely lasts long and even within such circumstances they try to do each other down. Seymour gives the example of imperialist intervention in Russia after 1917, when they could agree on the need to intervene, but not to collaborate fully, for fear than one or the other imperialist would gain an advantage. Eventually the most reactionary wing of the German bourgeoisie armed the early Soviet state to gain a hoped-for advantage.

The ultimate example was in WWII and its leadup, when both imperialist axes tried to gain advantages over each other – and did so – by collaborating with their class enemy – the USSR – to defeat the other faction. As is well known, the US-led allies came out on top of the Third Reich by those means. Seymour cites the meeting between Hitler and French Ambassador Coulandre at the beginning of WWII, when both agreed that the war would likely lead to workers revolution (this was quoted by Trotsky in In Defence of Marxism). He quoted other examples, such as parts of the US bourgeoisie undermining sanctions against Cuba in the early Castro period because they could make profits from sugar.

Seymour generalises it thus, and his argument is completely orthodox Marxism:

“The issue was first posed sharply in the Marxist movement by Kautsky’s theory of ultra-imperialism, which held that competition between imperialist nations could be peacefully mediated in the same manner as competition between domestic monopolies. Lenin countered that the bourgeoisie cannot transcend national interests and that inter-imperialist agreements can only be based on the existing balance of strength which all parties are desperately seeking to change to their advantage.”

We can see this incapacity to overcome imperialist capitalism’s national basis today. The nearest thing to capital transcending national boundaries that has ever existed is the globalisation of the world economy since the collapse of Stalinism. Seymour had no knowledge of this when he wrote this essay in 1977.

US hegemony, which suffered some decline in the 1970s over Vietnam, massively expanded after 1991 to produce this phenomenon. But now it is being torn to shreds, by right-wing populist movements that reject most of its nostrums. Migration is one key cutting edge. The populists, where they are not fascists themselves, will ally with fascists on this. But there are other such cutting edges.

The collaboration of imperialist states in wars that many of the nationalist-minded factions regard as being of dubious value to them, has become a target. Nationalist opposition to the Ukraine war, which the populist factions see as a project of the ‘globalists’, is an example. If this is not correctly understood by the left, we risk being disarmed in the face of this.

The right-wing forces that are opposing the Ukraine proxy war are not progressive. They are not our allies, as some on the left think. They are simply re-asserting the indissoluble connection of imperialist capitalism with the imperialist nation-state and rejecting globalisation as in effect a deviation from that.

The likes of Trump, Farage, Le Pen, the German AfD, Salvini in Italy, are our strategic imperialist enemies. Any resemblance of what we say to what they say is entirely superficial. Our job is to provide an internationalist alternative to them in opposing the wars of the other faction, not to conciliate them. Our job is not to unite with them, but to independently fight against the imperialist wars and proxy wars that we face, in order to tear the masses away from these nationalist factions and win them to an internationalist position. That is crucial.