The notes for this presentation (5th January) are now available to read, and the presentation and discussion are also available to listen to as a podcast.

This presentation, by a Consistent Democrats speaker, and the discussion that followed it, is available as a podcast also.

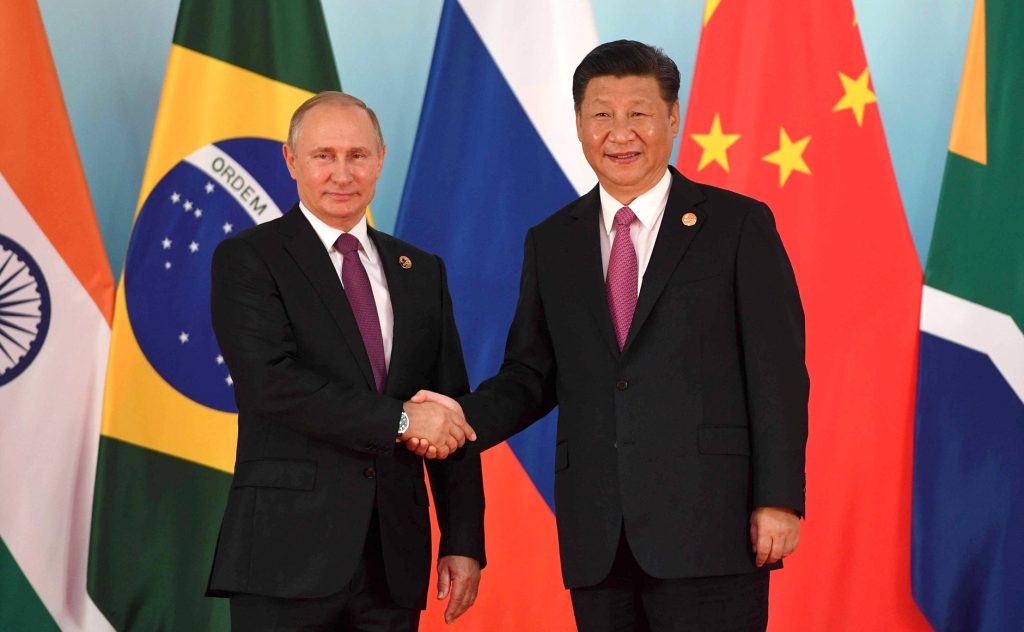

This talk focuses on the nature of Russia and China today. It is based on the LCFI’s statement “Marxism and the Post-Counterrevolution Cold War” from just over a year ago. This is the beginning of the subject. We undoubtedly need more discussions to deal with the world situation today, and the road to world revolution. These are huge issues. We are living through a new historical period

The imperialist powers of European origin (with the sole exception of Japan), the monopoly capitalist powers that have enriched themselves and dominated the greater part of the globe, for approximately 150 years, have gone into the greatest crisis in their history. And what is remarkable is that this crisis is manifesting itself only 30 years or so after imperialist capitalism had achieved what seemed to be its greatest triumph. In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed, and the former multinational degenerated workers state fragmented along national lines.

In Russia, its central component, a government came to power led by Boris Yeltsin, the former chief of the Moscow Communist Party, who had metamorphosed into first a populist demagogue, and then an advocate of the restoration of capitalist through a massive, rapid economic shock. The marketising regime of Mikhail Gorbachev, which whittled away at central planning in the name of perestroika (reconstruction) and which did away with the repression of the Stalinist regime in the name of glasnost (openness), acted a transitional ‘bridge’ to the rise of Yeltsin and the counterrevolution. This Yeltsin catastrophe happened less than two years after Gorbachev opened the Berlin wall, which resulted in the coming to power of capitalist restorationist regimes, liquidating the deformed workers states of Eastern Europe, with Poland under the pro-capitalist trade union, Solidarność, as the vanguard.

Parallel with this we had the rise of capitalism in China. Even though the Communist Party remained in power, since 1979 and the rise to power of Deng Xiaoping as leader of the party, a kind of pro-capitalist ideologue as well as being a ‘Communist’ bureaucrat. His regime broke the ‘iron rice bowl’, the system of collective welfare that was the foundation of the Chinese deformed workers state under Mao since the 1949 revolution. The watchword of Deng was ‘to get rich is glorious’: marketisation in China accelerated more quickly in China than in the USSR throughout the 1980s. Though the final breakthrough for capitalist restoration was controlled by the bureaucracy from above, not through a shock treatment directed at the bureaucracy externally, as in Russia. But through a massive intensification of marketisation/privatisation promoted by Deng on his Southern Tour in late 1992, which beat back the backlash within the bureaucracy against marketisation that occurred after Tien-An-Mien Square in 1989, and represented a qualitative turning point. So that is the initial background of the counterrevolutions in the main deformed workers states.

So, this educational is about the character of Russia and China today. Everyone above a certain age remembers the Cold War, most likely Cold War II, the warmongering crusade against Communism and the USSR led by Ronald Reagan. The hysterical, warmongering response to the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in December 1979 is part of what won me to Trotskyism. The West provoked the Soviet intervention by funding and arming counterrevolutionary forces against a reforming government, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan. The warmongering hysteria today over Russia’s SMO in Ukraine is certainly reminiscent of the Carter-Reagan warmongering over Afghanistan, as is their support of far-right extremist forces.

Similarly, what in the Ukraine, Georgia, or Hong Kong context are today called ‘colour revolutions’ – orchestrated and well-funded mass coup movements that are intended to overthrow governments – even elected ones – that the west disapproves of. These are somewhat familiar from the 1980s when the West funded counterrevolutionary movements in Eastern Europe – Polish Solidarność was the best-known example. A movement of workers, to be sure. But unlike the situation in the 1950s, when Hungarian and Polish workers rose up and demanded democratised workers states and workers control, in 1980 onwards Solidarność rapidly consolidated around a pro-capitalist, neoliberal programme. Such movements are familiar today, as are what they lead to.

What needs explaining is that capitalism, of a sort, is now dominant in the main former workers states, i.e. Russia, which does not claim to be socialist. And China, (whose Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping, is actually a dollar billionaire, with $1.2 billion according to Forbes). That is the legacy of the counterrevolutions of 1989-92. And yet the warmongering, crusade in Western countries against Russia and China is just as intense as it was in the Cold War of the 1980s, and for those old enough to remember, the Cold War of the 1950s also. Why is this?

It is because capitalist restoration has not proved as straightforward as the ideologues of Western imperialism made out in 1989, as exemplified by Francis Fukuyama and his essay “the End of History”. Marx’s vision was that human society would end its series of social transformations and revolutions, from primitive communism, which fell when humanity divided into classes, through slave- based production, then feudalism, through capitalism, to the final abolition of classes and the creation of developed communism. Fukuyama’s fatuous version had liberal imperialist capitalism in that role. A monstrous form of exploitation, not only of the working class in the advanced countries, but robbery of the bulk of humanity in the oppressed Global South, to extract the wealth that fuels the privileged position of the imperialist countries. Fukuyama’s vision was a complete insult to the bulk of humanity.

And to the population of the former USSR, particularly the population of Russia, who as part of this ‘end of history’ nonsense, were subject to a Pinochet-like neoliberal economic shock under Yeltsin that caused deaths by starvation, and suicide in the face of starvation, to Russian workers. This caused a fall in life expectancy of over 5 years in the early-mid 1990s, which can only be explained by millions of premature deaths. This resulted in a massive popular backlash from below. Which the Russian state responded to, giving rise to Putin’s who has become hated by imperialism because of his reversal of many of Yeltsin’ attacks. He is hated for this, not for ‘authoritarianism’. Similar things happened in China also, which also managed to make use of Western outsourcing to build itself industrially, using its state apparatus – derived from decades when it was a workers’ state. And has become the world’s industrial powerhouse.

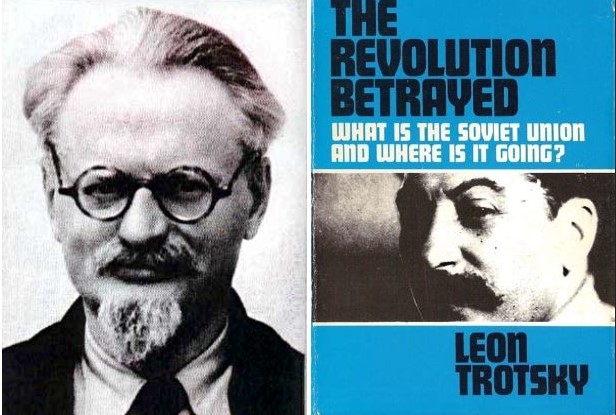

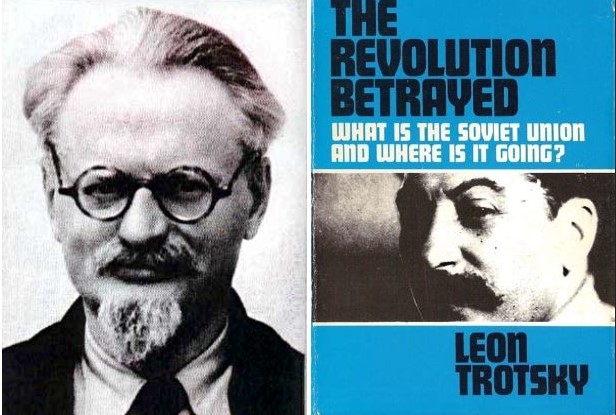

We have been studying Leon Trotsky’s The Revolution Betrayed. We will not repeat here Trotsky’s analysis of the reasons for the rise of the bureaucratic caste in the USSR in in 1920s and 30s. Neither will we analyse the Chinese revolution of 1949, except to note that the workers state it created was not in the image of the early Soviet state of Lenin and Trotsky, literally a state of democratic workers councils, but rather one like Stalin’s USSR where the working class was deprived of power by kind of labour bureaucracy, right from the start. It was a sort of clone of Stalin’s USSR, not Lenin and Trotsky’s.

Trotsky foresaw that the bureaucratisation of the Soviet Union would lead to capitalist restoration. He was proved right, though not in his own lifetime. His warnings only came to pass decades after his death. Nevertheless, he was compelled to sketch out some basic features of such a counterrevolution. He wrote an important essay in 1937 titled: Not a workers’ and not a bourgeois state. I will quote some passages which shed light on what he considered likely:

“The proletariat of the USSR is the ruling class in a backward country where there is still a lack of the most vital necessities of life. The proletariat of the USSR rules in a land consisting of only one-twelfth part of humanity; imperialism rules over the remaining eleven-twelfths. The rule of the proletariat, already maimed by the backwardness and poverty of the country, is doubly and triply deformed under the pressure of world imperialism. The organ of the rule of the proletariat – the state – becomes an organ for pressure from imperialism (diplomacy, army, foreign trade, ideas, and customs). The struggle for domination, considered on a historical scale, is not between the proletariat and the bureaucracy, but between the proletariat and the world bourgeoisie… For the bourgeoisie – fascist as well as democratic – isolated counter-revolutionary exploits … do not suffice; it needs a complete counter-revolution in the relations of property and the opening of the Russian market. So long as this is not the case, the bourgeoisie considers the Soviet state hostile to it. And it is right.

“The internal regime in the colonial and semicolonial countries has a predominantly bourgeois character. But the pressure of foreign imperialism so alters and distorts the economic and political structure of these countries that the national bourgeoisie (even in the politically independent countries of South America) only partly reaches the height of a ruling class. The pressure of imperialism on backward countries does not, it is true, change their basic social character since the oppressor and oppressed represent only different levels of development in one and the same bourgeois society. Nevertheless the difference between England and India, Japan and China, the United States and Mexico is so big that we strictly differentiate between oppressor and oppressed bourgeois countries and we consider it our duty to support the latter against the former. The bourgeoisie of colonial and semi-colonial countries is a semi-ruling, semi-oppressed class.

“The pressure of imperialism on the Soviet Union has as its aim the alteration of the very nature of Soviet society… By this token the rule of the proletariat assumes an abridged, curbed, distorted character. One can with full justification say that the proletariat, ruling in one backward and isolated country, still remains an oppressed class. The source of oppression is world imperialism; the mechanism of transmission of the oppression – the bureaucracy. If in the words ‘a ruling and at the same time an oppressed class’ there is a contradiction, then it flows not from the mistakes of thought but from the contradiction in the very situation in the USSR. It is precisely because of this that we reject the theory of socialism in one country.”

This juxtaposition of the situation of the semi-colonial capitalist ruling classes, with that of the proletariat in power in a backward and isolated workers state, is highly suggestive of what Trotsky considered likely to happen in a counterrevolution. In a situation where the proletariat in power was oppressed by imperialist encirclement and backwardness, any bourgeois regime that were to replace it would face the same material conditions, and would likewise be a “semi-ruling, semi-oppressed class”, subject to imperialism.

Trotsky also had some useful observations about the course of counterrevolution, actual and likely, in the context of both the French (bourgeois) and Russian (proletarian) revolutions in an earlier (1935) piece, The Workers State, Thermidor and Bonapartism. Talking directly about the French revolution, he wrote:

“After the profound democratic revolution, which liberates the peasants from serfdom and gives them land, the feudal counterrevolution is generally impossible. The overthrown monarchy may reestablish itself in power and surround itself with medieval phantoms. But it is already powerless to reestablish the economy of feudalism. Once liberated from the fetters of feudalism, bourgeois relations develop automatically. They can be checked by no external force; they must themselves dig their own grave, having previously created their own gravedigger.”

He contrasted that with what would be likely in the event of the collapse of the Stalinist regime and the Russian revolution with it:

“It is altogether otherwise with the development of socialist relations. The proletarian revolution not only frees the productive forces from the fetters of private ownership but also transfers them to the direct disposal of the state that it itself creates. While the bourgeois state, after the revolution, confines itself to a police role, leaving the market to its own laws, the workers’ state assumes the direct role of economist and organizer. The replacement of one political regime by another exerts only an indirect and superficial influence upon market economy. On the contrary, the replacement of a workers’ government by a bourgeois or petty-bourgeois government would inevitably lead to the liquidation of the planned beginnings and, subsequently, to the restoration of private property. In contradistinction to capitalism, socialism is built not automatically but consciously…”

“October 1917 completed the democratic revolution and initiated the socialist revolution. No force in the world can turn back the agrarian-democratic overturn in Russia; in this we have a complete analogy with the Jacobin revolution. But a kolkhoz overturn is a threat that retains its full force, and with it is threatened the nationalization of the means of production. Political counterrevolution, even were it to recede back to the Romanov dynasty, could not reestablish feudal ownership of land. But the restoration to power of a Menshevik and Social Revolutionary bloc would suffice to obliterate the socialist construction.”

But what happened is more complex. We have had something like “the replacement of a workers’ government by a bourgeois or petty-bourgeois government … ” and “….the restoration of private property” in Russia since the 1991 collapse of the USSR. In China, we have had policies carried out for decades that Trotsky considered would lead to the rapid collapse of the Soviet Union into a kulak-led counterrevolution in the late 1920s. By the standards of the struggle of the Left Opposition against the Stalin-Bukharin bloc and its Neo-NEP – it is inconceivable that the regime of the Chinese Communist Party, with its numerous billionaire capitalists whose influence penetrates to the very top of the CCP regime, could be described today as a workers’ state.

And yet far from stabilising world capitalism under the rule of the imperialist bourgeoisie, we now have a considerable level of unity in defensive struggle of the two giant former workers states of Russia and China, against US/led NATO imperialism, which grows more and more hysterical every day. Why is this? We would reply that as with anticipations and theorisations by Marxists of what might happen if a workers revolution triumphed in a backward country, the theorisations of what would happen if such revolutions were subsequently defeated, by even the best Marxist theoreticians including Trotsky, have proven inadequate.

Trotsky was correct to say, of the bourgeois revolution, that “once liberated from the fetters of feudalism, bourgeois relations develop automatically”. However, that does not transfer to a situation where it is not feudalism that is overthrown by capitalism, but a workers’ state based on socialised property. When degenerated and deformed workers states have been overthrown by pro-capitalist forces, it has not been the case, unlike with feudalism, that “bourgeois relations develop automatically”. What we have seen is that these “bourgeois relations” have been problematic and given rise to forms of society that the imperialist bourgeoisie does not trust. States have emerged that contain enough modifications of those features of capitalism as a system that the imperialists consider vital and non-negotiable, that the same imperialists fear that these societies could flip back to some sort of socialist construction.

Perhaps like 19th Century France did to bourgeois-revolutionary upheavals after the defeat of Napoleon, with its supplementary revolutions in 1830, 1848 – which convulsed the whole of Europe – and 1871 – which gave rise to the Paris Commune, the first attempt in history to create a workers’ state.

What has come into existence in those workers states where indigenous social revolutions were once victorious and defeated many decades later, are capitalist states, but ones where capitalist relations are modified and ‘deformed’ in significant ways, and those states do not function either as imperialist states, or as semi-colonial vassal states. Neither Russia nor China fit into either category. Nor do they occupy any intermediate category between the two – they are qualitatively different from both. This is very different to passively produced ‘satellite states’ like most in East Europe, which have generally become satellites/vassals of Western imperialism.

What is at the root of this? One hint of an answer can be found in a formulation in Engels’ 1880 work Socialism Utopian and Scientific, where he makes the following point about the tendency of capitalism towards the generation of trusts and monopolies:

“In the trusts, freedom of competition changes into its very opposite — into monopoly; and the production without any definite plan of capitalistic society capitulates to the production upon a definite plan of the invading socialistic society. Certainly, this is so far still to the benefit and advantage of the capitalists. But, in this case, the exploitation is so palpable, that it must break down. No nation will put up with production conducted by trusts, with so barefaced an exploitation of the community by a small band of dividend-mongers.”

This formulation, about the ‘invading socialistic society”, stems from the basic idea of Marxism, held in common by Marx and Engels, that “socialism” or “communism” which they considered as two manifestations of the same thing (‘lower’ and ‘higher’) represented a superior mode of production to capitalism. As Marx wrote in Capital:

“Development of the productive forces of social labour is the historic task and justification of capital. This is just the way in which it unconsciously creates the material requirements of a higher mode of production.”

Much of Trotsky’s polemic against the Stalinists in the 20s and 30s was against the theory of socialism in one country, the notion that it was possible to build a complete socialist mode of production in a society qualitatively more backward than the far stronger capitalist-imperialist powers that encircled it. That critique retains its full relevance and potency. But then again, Trotsky also noted that despite this, the reactionary course of the Stalinist regime “… has not yet touched the economic foundations of the state created by the revolution which, despite all the deformation and distortion, assure an unprecedented development of the productive forces.” (Once Again: The USSR and Its Defence)

Engels considered that the socialist mode of production, which was completely in the future in 1880 when he wrote Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, had the ability to ‘invade’ contemporary capitalism, and as a kind of unconscious expression of the historical process, affect the development of the same capitalism to (in some ways) anticipate future developments that would come to fruition under a higher mode of production. This is only an expression of the basic Marxist concept that Socialism: Utopian and Scientific expresses — the objective tendency of social development toward socialism. The point being that the process of capitalist restoration, the destruction of a long-established workers state, cannot be ‘automatic’ in the manner in which capitalism is able to do away with feudalism.

The existence of a workers’ state, however deformed or degenerated, means that that state has already begun the transition to a higher mode of production, communism. Even if the transition is blocked by social backwardness, imperialist encirclement and the monopoly of power of a bureaucracy that opposes and attempts to sabotage the world revolution and thereby the completion of the transition, the transition has begun. The train has left the station, even if it is stalled only a few hundred yards down a track that is many miles long. It is extremely heavy, and still very difficult to simply drag back to its starting point and beyond.

Therefore, what we have in both Russia and China are new social formations where the capitalist mode of production managed to defeat the social formation of the previous transition process, but, however, is forced to coexist in this phase with elements of an “invading socialistic society” that profoundly change those societies. Previous revolutionary processes initiated some kind of transition to the communist mode of production. These processes did not develop in the form of a linear evolution, they were interrupted and sabotaged by the siege of capitalism, imperialism and the internal contradictions originating from this siege.

Within a social formation, more than one mode of production can coexist, in an unequal and combined way. In this case, the post-capitalist mode of production coexists with ‘elements’ (of a “invading socialistic society”) of deformed proletarian dictatorships, which are, at the same time, the germ of a future socialist mode of production. It is important to remember, that in much of the semi-colonial world, capitalism coexists with a pre-capitalist heritage. That is the basis of the whole rich programmatic heritage of Permanent Revolution. Now in China and Russia various forms of capitalism coexist with a post-capitalist heritage.

There is a classic, dialectical quality in the reality that the outcome of the counterrevolution that destroyed deformed workers’ states, is a form of capitalist state that itself embodies major deformations and modifications that stem from their decades without capitalism, to the extent that imperialism perceives them as a major threat to their rule and their hegemony.

The notes for this presentation (20th October) are now available to read, and the presentation and discussion are also available to listen to as a podcast.

This is the presentation (with some edits and corrections) that was given by a Consistent Democrats speaker at our educational on 21st July. The recording of the meeting is also available as a podcast, and can be found here.

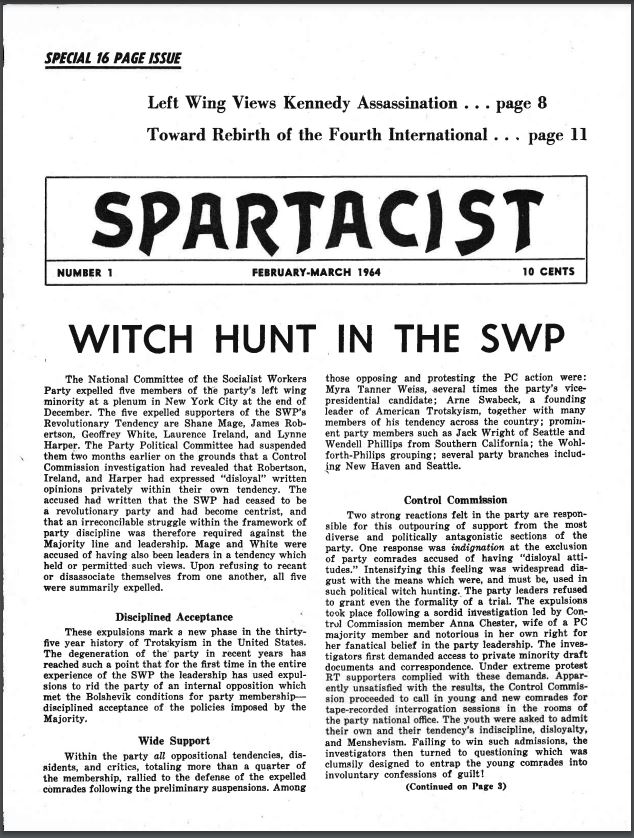

The essay that this educational is about was a seemingly abstract commentary made by Joseph Seymour, key intellectual figure of the Spartacist League of the United States in the mid-1970s. The old Spartacists were a contradictory political trend with roots in both of the two major trends in the US that emerged from the Trotskyist movement in Trotsky’s day.

The US Trotskyist movement had been founded in the late 1920s by three prominent members of the US Communist Party: James P Cannon, Martin Abern and Max Shachtman. The US Left Opposition and its successors – most notably the US SWP – always worked very closely with Trotsky and carried out many of the tactics of the Trotskyist movement in the years before the founding of the Fourth International in 1938. It did serious work in the trade unions. In 1934, its trade union militants led the Teamsters’ (truckers) strike in Minneapolis, one of three major strikes that year led by Communist groups in the period of revival of the workers movement after the worst of the Great Depression. And it carried out a short-term entry into the Socialist Party in 1936-7, which enabled it to fuse with a layer of younger militants.

In some ways, the SWP – a thousand or so people – became the leading party of the Fourth International when it was founded in 1938. Their geographical closeness to Mexico was an advantage in collaborating with Trotsky in his final exile. They were also subjected to the pressures which the whole of the movement was subjected. Because of the relatively open situation they lived in, the issues were fought out in the open.

The Stalin-Hitler pact in 1939 caused splits in the Trotskyist movement. A wave of hysterical Stalinophobia, that equated Stalin’s regime with Hitler’s, swept the labour movement in the imperialist countries. In the US, a faction led by Shachtman, Abern and James Burnham (an academic figure) was formed, which abandoned defence of the Soviet Union against imperialism. By the end of the dispute in 1940 Shachtman had developed the theory of bureaucratic collectivism, the USSR as a new class society, neither capitalist nor socialist, but worse than capitalism.

Cannon, and the core trade union cadre of the SWP, joined with Trotsky to defend the USSR as a degenerated workers’ state. These issues were fought out comprehensively. Two important books are availble on this: Trotsky’s In Defence of Marxism, and Cannon’s The Struggle for a Proletarian Party.

In 1940 Trotsky was assassinated. The Trotskyist movement faced WWII without his insights. The complex sequence of events in WWII led to the defeat of Nazi Germany and its allies, Italy and Japan, primarily by the USSR in alliance with the US, with Britain and France in tow. The situation after the war was a mess. The Stalinists defeated Nazi Germany, but also made sure that the working class as an independent class did not come to power anywhere. Wherever the working class threatened to come to power directly, the Stalinists united with imperialism to crush it. Most notably in Europe, in France, Italy and Greece in Europe, and in Vietnam with the Saigon workers insurrection in 1945.

But there was also the unstable phenomenon of the creation of deformed workers states, in East Europe, China, and elsewhere. The Trotskyist movement was disoriented by the creation of these states without the conscious action of the working class. The imperialists were implacably hostile to the USSR’s victory and the new deformed workers’ states and set up NATO as an aggressive instrument to fight them. The Cold War ensued.

After the war, without Trotsky’s guidance, the Trotskyist movement partly capitulated to Stalinism, and many began to hail bureaucratic Stalinist leaders as revolutionaries who would lead the world revolution. Others followed in the footsteps of Shachtman and capitulated to imperialism. There was little coherent understanding of what had happened. There were a lot of very complex and confused debates. The Sparts represent one fragment of these debates. They got possibly the trickiest problem right, that of Cuba. Which ought to have laid the basis for resolving all these problems. But it was not to be.

Fidel Castro and his guerrilla movement came to power in 1959 and overthrew a classic US-backed neocolonial tyranny. Then they proceeded to nationalise virtually the entire Cuban economy to preserve themselves from being overthrown by the Cuban bourgeoisie who simply worked with US imperialism. Some Trotskyists, including the ageing US SWP cadre, hailed Castro as an unconscious Marxist and world revolutionary. Others denied that there had been a revolution in Cuba at all.

The Spartacists got this right and understood that while Cuba was a workers’ state and had expropriated capital, it was a deformed workers state that needed a supplementary political revolution to bring the working class to genuine political power. Castro had come to power at the head of a movement that was not initially communist even in name. He was a liberal, who emerged from the Orthodoxo Party. Yet in power, his July 26 movement changed its ideology to match what it had done and joined the Soviet bloc. Their understanding of Cuba clarified what a deformed workers state was.

Such states had been generally created by communist movements that had abandoned the working class, based instead on an oppressed peasantry, and that these parties had become petty-bourgeois nationalist parties. When the working class was politically paralysed and under extreme conditions of imperialist oppression, such movements proved capable of overthrowing capitalism and creating such workers’ states, but with a fundamental weakness, that was later to destroy most of them. I.e, an anti-working class, bureaucratic regime, committed to socialism in one country, similar to the USSR under Stalin and since. In Cuba, however, unlike all the other examples where such states were created independently of simple conquest by the USSR, the movement that carried this out was not even formally communist before the revolution. This was clarifying as to what was really involved in the others, such as China, Yugoslavia, etc. This was a very perceptive and thoughtful analysis. No one else developed it at the time.

The Spartacists in the decades to come used this to argue that they were the continuity of Cannon’s SWP in its best period, created under Trotsky’s guidance, and therefore the only real Trotskyists in the world. This had some apparently credibility in their earlier period, but this was incorrect, a conceit based on a partial understanding, that slowly drove them mad. It was wrong, because they were rooted in both strands of the pre-war movement. The founders of the Sparts, particularly Roberston and also Wolhforth, who played the key role in the creation of this trend, came from Shachtman’s anti-Soviet Workers Party, not the SWP.

They joined the ageing, rightward-moving SWP in the mid-1950s, on the basis of being won to orthodox Trotskyism on the Russian question, and later were thrown out for being right about Cuba. But Roberston, who became the leading figure, though he had broken from Shachtman over the Russian question, had not questioned another aspect of Shachtman’s politics: his left-Zionism. As part of their right-wing evolution at the beginning of the Cold war, the Shactmanites had supported the creation of Israel. That was another political strand.

In the coming decades the Sparts produced orthodox material on the Russian question, given weight by their correct understanding of Cuba, for instance their opposition to Solidarnosc in the 1980s. But this correct politics was mixed with material on Israel/Palestine that in the earlier period sided with Israel. They also copied that approach and tried to apply it to the Irish question from the late 1960s. Originally, they were (in a strange way) pro-Unionist in Ireland. In 1973, trying to address the Irish struggle that had raged since 1968, they called for a independent Ulster, supposedly as part of a ‘socialist’ programme to unite Ireland! Later they modified their positions to be effectively neutral in these national struggles. Calling on Arab and Jewish workers in Palestine, or Nationalist and Unionist workers in the North of Ireland, to abandon their national struggles and unite. Not much of an improvement. They were a perplexing phenomenon, because they were partly right, and partly severely wrong. Which is very damaging, as an old saying has it, a half-truth is more damaging than an outright lie. This contradiction gave rise to an organisation with a strange and damaging way of working, a reflection of their political contradictions.

But they were sometimes capable of great insight. Seymour’s article is a startling example. Seymour’s article steers completely clear of any superficially complex colonial questions. It leaves that aspect of Spartacist politics completely alone. That is its strength. Instead, it deals with the problem of how the class consciousness of the imperialist bourgeoisie works and attacks some misconceptions of this that are common on the left. He contrasts different concepts of left reformism about how capitalist society works. The structural concept and the conspiracy concept.

For some reformists capitalism is purely a matter of a structure. All you have to do is change the structure and society will improve incrementally. There is no sense in this that there are real material interests that dictate these structures, i.e. property relations that reflect the interests of a specific layer – the capitalist ruling class.

And there is the view that capitalism itself works through a series of conspiracies. The job of socialists is therefore to combat and expose the conspiracies. This may seem very radical, but it is flawed, and can also lead to a pessimistic view. There are a lot of those concepts around now, both on the right and on the left, in different forms.

You hear those who attach great importance to the World Economic Forum, who are seen as so advanced and the real rulers of the planet, somewhat different to the ruling class itself. An earlier example is the whole series of similar theories about the Bilderberg group. The ‘Great Reset’ theory is linked to the theories about the WEF and presupposes some demonic scheme – the leftist variant being to destroy all previous gains of the working-class movement. The right-wing variant of this has theories of the ‘replacement’ of the population of the imperialist countries with immigrants. Both of these found common ground in various theories about the Covid pandemic, that this was part of some sinister scheme to do one or the other of these things, according to the particular leaning of the theorists. This blurred the difference between left and right. It has to be said that as their organisation collapsed around 2020, and then created a new leadership, the Spartacists seemed to go through some strange political-psychological process where they seemed lost in paranoia about the Covid pandemic.

But as Seymour points out, the bourgeoisie does not have the level of coherence that such theories imply. These various think-tanks are partial. They are the brainchild of various bourgeois milieux who are fallible and capable of misunderstanding reality as much as any other group of bourgeois. If your world view is that the class struggle depends on who can organise the most effective conspiracies, it is not a huge step from this to the view that the bourgeoisie is too clever and capable of organising conspiracies to be overthrown. That leads by another route to submission to bourgeois authority, and instead attempts to convince the bourgeoisie to mend their ways. To another form of reformism, in other words.

Monopoly capitalism is getting more and more concentrated. And firms connected by neoliberalism, venture capital and banking are getting more and more powerful. Examples do exist of a worldview where capitalist society can jump over the law of value. Modern Monetary Theory is such a position. The idea that ‘fiat’ currencies are almost infinitely expandable, provided they can be kept essentially separate from other currencies.

The bourgeoisie are not conspiratorialists who run the world according to a plan. They are not Marxists in reverse, and Seymour is at pains to emphasise this. Their real aim is to realise surplus value, or to put it more simply, to make profits. They are quite capable of forming factions on a large or small scale to do each other down, or to crush or even in extremis to slaughter each other, via ‘their’ workers, in inter-imperialist wars, if they feel it necessary from their own particularist standpoint. Their ideology is not Marxism looked at from the other end of the telescope. They do not apply reverse class struggle concepts in any scientific manner to the class struggle from their side. Individuals may boast of doing such things, but bourgeois class-war tactics are empirical, and may undermine their own interests in the future.

For instance, Thatcher’s destruction of heavy industry in Britain was straightforwardly done to undermine what was in the 1970s the strongest trade union movement in Europe. It succeeded. But in doing so, it accelerated Britain’s decline as an imperialist power enormously. Something similar happened in the US. Much productive capacity was outsourced to China and other low wage countries to cut down on labour costs. China gained a lot from that. Now all factions of the US bourgeoisie regard China as a major threat. This is not smart.

The bourgeoisie persists in this behaviour, it cannot do otherwise, it is how it thinks. Social being determines social consciousness. Various ex-Marxist ideologues have chided the bourgeoisie with such short-sightedness. James Burnham, after he broke from the US SWP and moved rapidly to the right from Marxism to right-wing cold war militarism, wrote a book called The Suicide of the West which as Seymour said was:

“…designed to prove that the dominant political attitudes of the American ruling class were optimistically false.”

He was ignored, and in part ridiculed. The bourgeoisie is episodically capable of class unity when confronted with a potent threat from the working class, but that rarely lasts long and even within such circumstances they try to do each other down. Seymour gives the example of imperialist intervention in Russia after 1917, when they could agree on the need to intervene, but not to collaborate fully, for fear than one or the other imperialist would gain an advantage. Eventually the most reactionary wing of the German bourgeoisie armed the early Soviet state to gain a hoped-for advantage.

The ultimate example was in WWII and its leadup, when both imperialist axes tried to gain advantages over each other – and did so – by collaborating with their class enemy – the USSR – to defeat the other faction. As is well known, the US-led allies came out on top of the Third Reich by those means. Seymour cites the meeting between Hitler and French Ambassador Coulandre at the beginning of WWII, when both agreed that the war would likely lead to workers revolution (this was quoted by Trotsky in In Defence of Marxism). He quoted other examples, such as parts of the US bourgeoisie undermining sanctions against Cuba in the early Castro period because they could make profits from sugar.

Seymour generalises it thus, and his argument is completely orthodox Marxism:

“The issue was first posed sharply in the Marxist movement by Kautsky’s theory of ultra-imperialism, which held that competition between imperialist nations could be peacefully mediated in the same manner as competition between domestic monopolies. Lenin countered that the bourgeoisie cannot transcend national interests and that inter-imperialist agreements can only be based on the existing balance of strength which all parties are desperately seeking to change to their advantage.”

We can see this incapacity to overcome imperialist capitalism’s national basis today. The nearest thing to capital transcending national boundaries that has ever existed is the globalisation of the world economy since the collapse of Stalinism. Seymour had no knowledge of this when he wrote this essay in 1977.

US hegemony, which suffered some decline in the 1970s over Vietnam, massively expanded after 1991 to produce this phenomenon. But now it is being torn to shreds, by right-wing populist movements that reject most of its nostrums. Migration is one key cutting edge. The populists, where they are not fascists themselves, will ally with fascists on this. But there are other such cutting edges.

The collaboration of imperialist states in wars that many of the nationalist-minded factions regard as being of dubious value to them, has become a target. Nationalist opposition to the Ukraine war, which the populist factions see as a project of the ‘globalists’, is an example. If this is not correctly understood by the left, we risk being disarmed in the face of this.

The right-wing forces that are opposing the Ukraine proxy war are not progressive. They are not our allies, as some on the left think. They are simply re-asserting the indissoluble connection of imperialist capitalism with the imperialist nation-state and rejecting globalisation as in effect a deviation from that.

The likes of Trump, Farage, Le Pen, the German AfD, Salvini in Italy, are our strategic imperialist enemies. Any resemblance of what we say to what they say is entirely superficial. Our job is to provide an internationalist alternative to them in opposing the wars of the other faction, not to conciliate them. Our job is not to unite with them, but to independently fight against the imperialist wars and proxy wars that we face, in order to tear the masses away from these nationalist factions and win them to an internationalist position. That is crucial.

The notes for this presentation (26th May) are now available to read, and the presentation and discussion are also available to listen to as a podcast.

To celebrate the anniversary of Victory Day, May 9th 1945 we publish these images. The first depicts the Soviet Red Flag being raised over the Reichstag by Soviet troops defending the USSR workers state against Hilter’s barbaric counterrevolutionary attack through the crushing of the Nazi regime.

Today, Russia is again winning victories against predatory Western attacks. The USSR workers state is no more, though the form of capitalism restored there is fragile; its productive forces and strength owe virtually everything to the legacy of many decades of non-capitalist social and economic development. The imperialist West fears that in Russia and China, for all the inroads that capitalism has made there, their system is not copper-fastened and the masses have too much power for their liking. To them, these states can easily revert and are thus adversaries to wage Cold and hot Wars against once again.

The other images show tropies of the victories of Russia in Ukraine, and the capture of Western tanks, that were recently put on display in Moscow. The hundreds of billions that have been funnelled to the Urainian Nazis have led to this Western humilation, which again is something to celebrate this Victory Day,

The notes for this presentation (28th April) are now available to read, and the presentation and discussion are also available to listen to as a podcast.

The notes for this presentation (7th April) are now available to read, and the presentation and discussion are also available to listen to as a podcast.